Updates: Climate Change

In his book The Third Horseman: A Story of Weather, War, and the Famine That History Forgot, historian William Rosen recounts the effect of the regional climate change on Europe in the early 1300s. His recounting of the history of Europe (but mostly England) in the wake of the “Little Ice Age” is fascinating and frightening. Political upheaval, inflation and famine are all magnified by the effects of a changing climate, while the uncertainty it brings dramatically alters the European landscape and its political status quo.

The little ice age saw a general cooling across much of Europe, a shortening of the growing season, an increase in heavy rains that flooded land, rendered marginal farmland unusable, and a spiking in grain prices forcing cereals to be sourced from farther away (like the middle east) to feed the northern parts of the continent. It also saw the loss of some industries, like England’s wine producers. The reputation for terrific French and Spanish wines, and the English reputation for drinking them in great quantities is forged in the shadow of the this geographically specific climate alteration.

Until now.

According to the Financial Times Britain is seeing a surge of vineyards opening, as far south as Sussex and as far north as Scotland. In 2023 the country recorded its largest ever grape harvest, while the country’s largest winemaker, Chapel Down, is looking to sell more shares to fund further expansion of its business.

Over the last decade I’ve made the case that climate change is really about water and its predictability. It is interesting to note that in the mass of worrisome predictions, of the potential for war, for famine, and for a less secure and more fragile world, that one of the less expected outcomes might be a change in cultural identity of a whole nation; that one rainy little island may stop being rainy, and undo 700 years of a cultural identity.

Updates: Real Estate

In 2020, one of the first things I wrote in at the beginning of the lockdowns was about the Canadian real estate market, and whether lockdowns and a pandemic might unravel our condo market. Though the lockdowns were long lived, Canadian real estate survived helped in large part by the extension of emergency levels of interest rates. The cost of living crisis and the housing bubble, ever intertwined, got worse, not better.

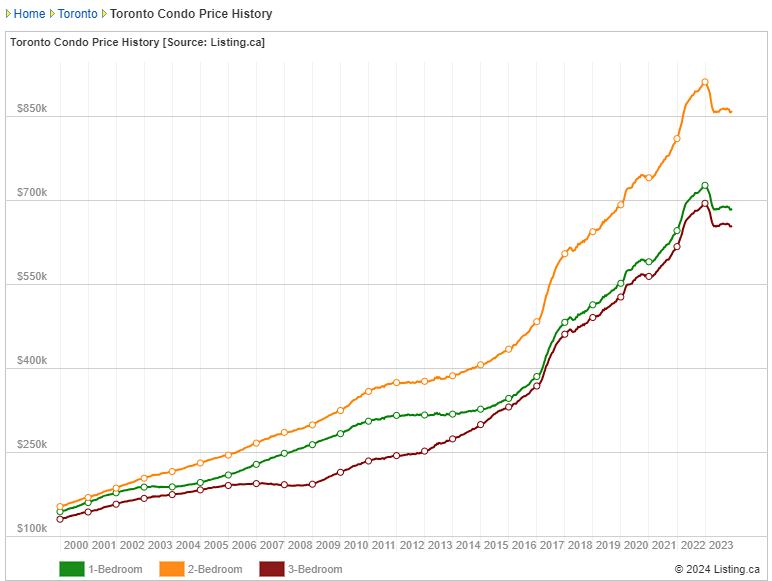

Condo prices reached their peak in January of 2023, and fell back to a current low by late April. Since then prices have fluctuated somewhat, but have been largely range bound. Reported by the Toronto Star on June 14th, “the number of new listings for condos has increased 30% since last May” the bulk of those in the investor size, ranging between 500 to 599 square feet. Urbanation, a trade publication for real estate states “In the past year, unsold new condominium supply increased 30%, rising 124% over the past two years.” In addition “projects in pre-construction during Q1-2024 were 50% presold, down from a 61% average absorption over a year ago, and 85% two years earlier.”

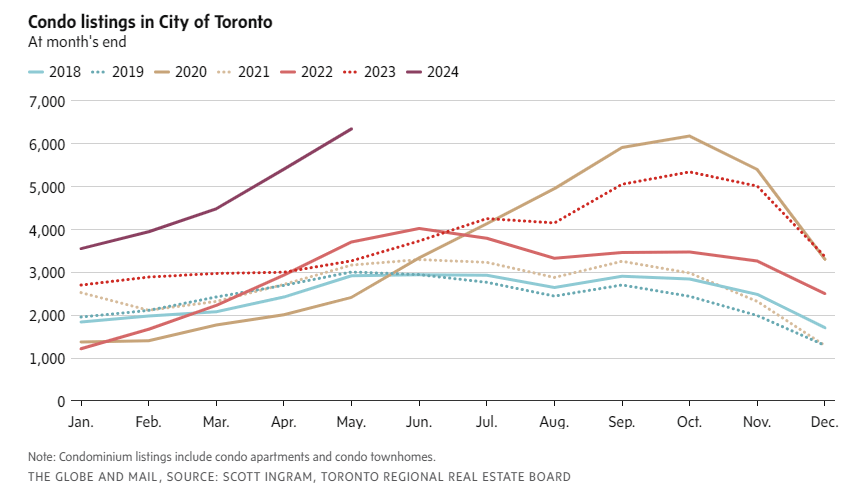

The Globe and Mail wrote on June 29th that “there were 6350 active condo listings in the city, an increase of 94% from the previous May” and that “condo inventory 70 per cent higher than the 10-year average for last month.” The deterioration in the condo market is being felt by existing owners and investors, as well as developers whose per square foot costs run roughly $500 higher than existing condo values.

All this seems to be aligning with a secondary real estate problem; office and commercial real estate. Across the United States as well as Canada office real estate is also struggling. Though not news, employees refusing to return to work and companies downsizing their real estate foot prints has had a significant impact on owners of office space. Banks are unloading office loans, REITs are trying to sell unprofitable assets, and some, like Slate Office RIET just defaulted on $158 million of debt. The story of real estate, once the most unflappable asset an investor could hold, continues to unfold in surprising and worrying ways.

Updates: Markets

With half the year behind us market performance has significantly diverged. US markets, being carried by the strong performance of NVIDIA as well as the handful of usual tech company suspects, have delivered shockingly great results. At the end of June the S&P 500 was up 14.48% so far. An impressive return, but 70% of those returns are from six companies, and 30% of the return is from just one. The S&P 500 Equal Weight return, an index that assigns each company a proportional weight, only has a return of 4.07%. That 70% difference in performance is down to Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Google (Alphabet), and Facebook (Meta).

The concentration of that performance makes the current rally fragile, though curiously other global indices, including Canada, are actually more concentrated than the US. This may account for why the TSX is only up 4.38% for the year, and had briefly dipped as low as 2.66% in June. Canadians are familiar with the feeling of having one of three industries (banking, energy, or materials) often set the tenor of a year’s returns. If the price of oil is climbing or falling, its often immediately reflected in our market index returns. In their own way the S&P 500 has taken on some of these characteristics.

Investors should know that markets continue to offer considerable upside, but those returns are coming from fewer and fewer parts of the economy.

Aligned Capital Partners Inc. (“ACPI”) is a full-service investment dealer and a member of the Canadian Investor Protection Fund (“CIPF”) and the Canadian Investment Regulatory Organization (“CIRO”). Investment services are provided through Walker Welath Management, an approved trade name of ACPI. Only investment-related products and services are offered through ACPI/Walker Wealth Management and covered by the CIPF. Financial planning services are provided through Walker Wealth Management. Walker Wealth Management is an independent company seperate and distinct from ACPI/Walker Wealth Management.

One explanation for this is that the labor participation rate has been very low and that the unemployment rate, which only captures workers still looking for work and not those that have dropped out of the workforce altogether, didn’t tell the whole story about people returning to the workforce. The result has been that there has been an abundance of potential workers and as a result there really hasn’t been the labor shortage traditionally needed to begin pushing up inflation.

One explanation for this is that the labor participation rate has been very low and that the unemployment rate, which only captures workers still looking for work and not those that have dropped out of the workforce altogether, didn’t tell the whole story about people returning to the workforce. The result has been that there has been an abundance of potential workers and as a result there really hasn’t been the labor shortage traditionally needed to begin pushing up inflation. The short version of this story is that Canadians are heavily in debt and much of that debt is sensitive to interest rates. Following a few rate hikes, insolvencies

The short version of this story is that Canadians are heavily in debt and much of that debt is sensitive to interest rates. Following a few rate hikes, insolvencies  Walking hand in hand is the increasing cost of education, and the declining returns it provides. In the United States the fastest growth in debt, and the highest rate of default is now found in student debt. According to Reuters the amount of

Walking hand in hand is the increasing cost of education, and the declining returns it provides. In the United States the fastest growth in debt, and the highest rate of default is now found in student debt. According to Reuters the amount of

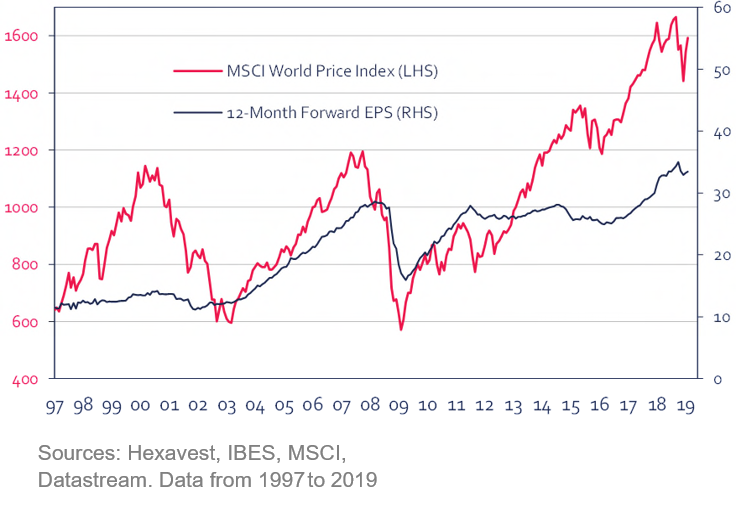

Efforts to hold off an actual recession though may have moved beyond the realm of political expediency. Globally there has been a slowdown, especially among economies that export and manufacture. But perhaps the most worrying trend is in the sector that’s done the best, which is the stock market. Compared to all the other metrics we might wish to be mindful of, there is something visceral about a chart that shows the difference in price compared to forward earnings expectations. If your forward EPS (Earnings Per Share) is expectated to moderate, or not grow very quickly, you would expect that the price of the stock should reflect that, and yet over the past few years the price of stocks has become detached from the likely earnings of the companies they reflect. Metrics can be misleading and its dangerous to read too much into a single analytical chart. However, fundamentally risk exists as the prices that people are willing to pay for a stock begin to significantly deviate from the profitability of the company.

Efforts to hold off an actual recession though may have moved beyond the realm of political expediency. Globally there has been a slowdown, especially among economies that export and manufacture. But perhaps the most worrying trend is in the sector that’s done the best, which is the stock market. Compared to all the other metrics we might wish to be mindful of, there is something visceral about a chart that shows the difference in price compared to forward earnings expectations. If your forward EPS (Earnings Per Share) is expectated to moderate, or not grow very quickly, you would expect that the price of the stock should reflect that, and yet over the past few years the price of stocks has become detached from the likely earnings of the companies they reflect. Metrics can be misleading and its dangerous to read too much into a single analytical chart. However, fundamentally risk exists as the prices that people are willing to pay for a stock begin to significantly deviate from the profitability of the company.

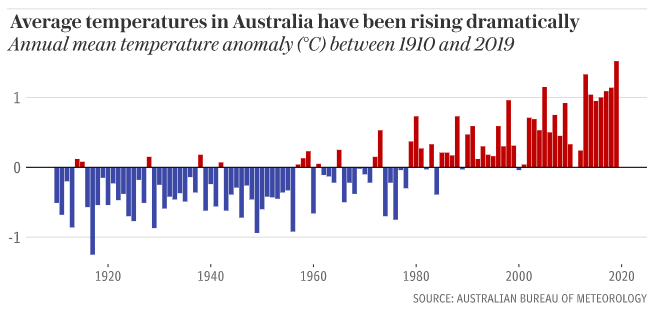

Australia, which has had years of heat waves, has recently faced some of the worst forest and brush fires imaginable (and currently bracing for more).

Australia, which has had years of heat waves, has recently faced some of the worst forest and brush fires imaginable (and currently bracing for more).

On the other hand chronic instability has a way of building in systems. One of the reasons that serious conflicts, political instability and angry populism haven’t done much to negate market optimism is because the nature of Western Liberal democracies is to be able to absorb a surprising amount of negative events. Our institutions and financial systems have been built (and re-built) precisely to be resilient and not fragile. Where as in the past bad news might have shut down lending practices or hamstrung the economy, we have endeavored to make our systems flexible and allow for our economies to continue even under difficult circumstances.

On the other hand chronic instability has a way of building in systems. One of the reasons that serious conflicts, political instability and angry populism haven’t done much to negate market optimism is because the nature of Western Liberal democracies is to be able to absorb a surprising amount of negative events. Our institutions and financial systems have been built (and re-built) precisely to be resilient and not fragile. Where as in the past bad news might have shut down lending practices or hamstrung the economy, we have endeavored to make our systems flexible and allow for our economies to continue even under difficult circumstances.