Back in the spring, markets reeled after Trump announced a new round of unilateral tariffs. The April 2nd announcement triggered a week of panic selling until the administration promised a temporary 90-day pause to pursue trade negotiations. Nine months later, the U.S. now has the highest tariff levels in over a century, economic data is showing signs of weakening, and discussions of a market bubble are widespread. Why, then, is the stock market still so high?

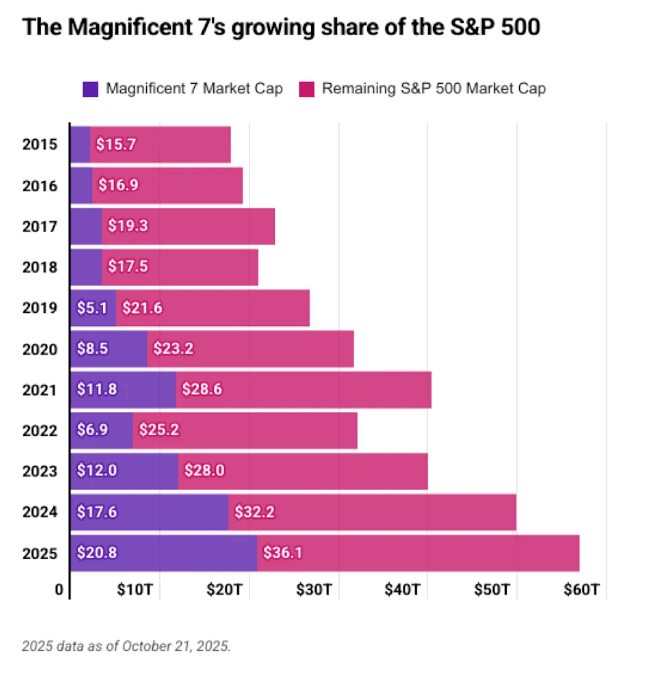

The most immediate reason is the concentration of market leadership. The “Magnificent Seven” tech giants now account for more than 35% of the S&P 500, while the top ten companies make up nearly 40%. The gap between the S&P 500 and its equal-weighted equivalent is just shy of 10%, while the Magnificent Seven themselves have delivered a combined return of roughly 27.6% year-to-date. The comparison to the dot-com era is easy to make, but the fundamental difference is profitability: Apple, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta and others continue to generate substantial earnings and hold enormous balance-sheet reserves. This profitability has helped anchor market confidence.

Another factor is the lag in how economic data reflects policy changes. Despite the risks tariffs pose, the full impact has not yet shown up in backward-looking data like GDP or employment reports. Investors expecting an immediate shock instead found resilient quarterly numbers, reinforcing confidence rather than shaking it.

There is also a deeper structural issue: the increasing concentration of economic power and spending. As wealth inequality widens, a large share of U.S. households are contributing less to measured economic activity. Recent consumer expenditure data suggests that the top 10% of households now account for roughly 50% of all consumer spending, while the bottom 60% contribute less than 20%. This means that economic stress among the majority of households may not meaningfully register in the headline data that markets rely on. Meanwhile, AI-related capital investment makes up a growing share of the remainder of measured economic activity.

This combination — delayed data effects, high concentration of consumption, and sustained AI investment — has helped keep investor sentiment resilient, even as negative signals accumulate beneath the surface. It has also masked the risks of allowing speculative dynamics to develop largely unchecked.

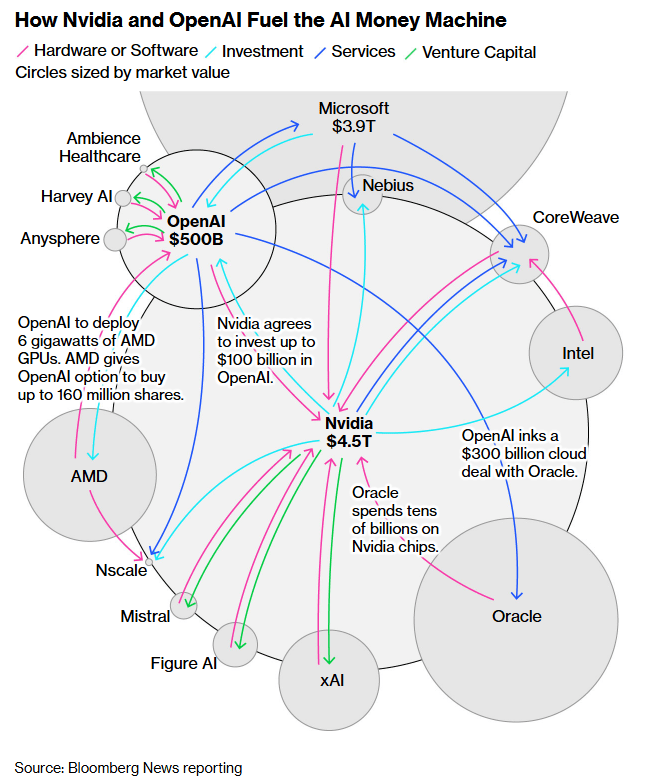

Concerns about an AI bubble are growing. Estimates of total AI investment now exceed $3 trillion when considering capital expenditures, valuations, and related infrastructure spending. Commercial use cases outside of a few sectors remain limited. Some firms have begun participating in “circular funding arrangements,” where they invest in each other’s AI initiatives to reinforce perceived valuations. Even industry leaders acknowledge the speculative environment: Sam Altman, the CEO of Open AI has said there is likely a bubble, while Jeff Bezos has called this a “good bubble” that will still produce transformative breakthroughs.

History suggests that speculative cycles are remarkably resistant to logic. They often convert skeptics into participants, including professional money managers who join in under client pressure. Market bubbles resemble the proverbial frog in a pot: the danger rises slowly enough to dull caution.

Yet they also resemble the “watched pot” that never seems to boil. As long as new capital continues to flow into AI-linked investments, momentum can persist. Predicting the end of a bubble is famously difficult — markets can remain irrational longer than investors can remain solvent.

So what should investors do? Awareness of rising risk is the starting point. We may not be able to time the end of the AI boom, but we can examine investor behavior for signs of speculative excess.

Consider Tesla. After the election, the stock surged nearly 98% in six weeks on enthusiasm linked to political alignment and narrative momentum. Since then, sales have weakened, profitability has declined, and competition has intensified — yet the stock remains 10% above its level on inauguration day and has more than doubled off its lows. Tesla’s valuation continues to reflect belief in future breakthroughs rather than current operational performance. It is a clear illustration of narrative overpowering fundamentals — a hallmark of speculative markets.

If this environment feels uncomfortable, it may be time to review portfolio risk exposure. Reducing equity risk comes with trade-offs — especially missing out on momentum-driven gains — but clarity on long-term goals can help prevent emotionally driven decision making.

Market manias are difficult to avoid and even harder to detach from when others are benefiting. The antidote is a disciplined investment plan that emphasizes long-term objectives over short-term excitement. In a world where the water may be warming around us, it is better to be a watcher than the frog.

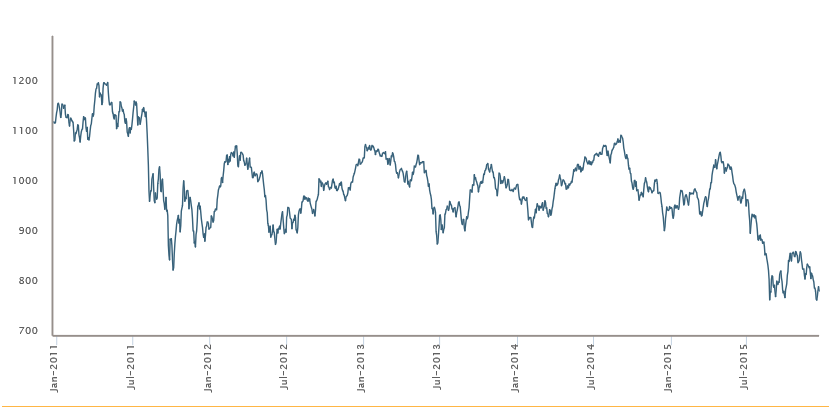

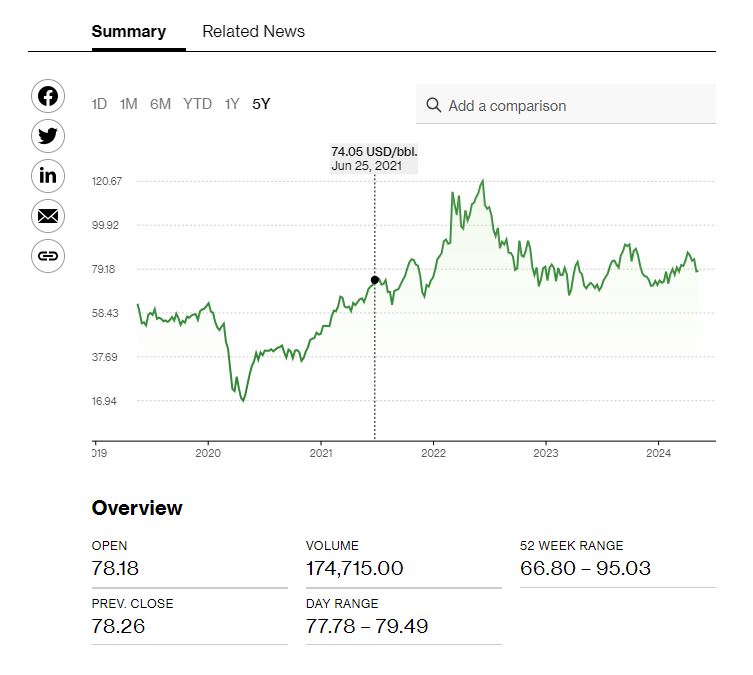

The first (and so far only) good day in the markets for 2016 shouldn’t go by without instilling some hope in us investors. The latter half of 2015 and the first weeks of 2016 have many convinced that the market bull is thoroughly dead, having exited stage left pursued by a bear (appropriate for January). The toll taken by worsening news out of China, falling oil, and the rising US dollar have left markets totally exhausted and despondent. But is the bull dead, or just mostly dead? Because there’s a big difference between all dead and mostly dead. In other words, is there a case to be made for a resurgence?

The first (and so far only) good day in the markets for 2016 shouldn’t go by without instilling some hope in us investors. The latter half of 2015 and the first weeks of 2016 have many convinced that the market bull is thoroughly dead, having exited stage left pursued by a bear (appropriate for January). The toll taken by worsening news out of China, falling oil, and the rising US dollar have left markets totally exhausted and despondent. But is the bull dead, or just mostly dead? Because there’s a big difference between all dead and mostly dead. In other words, is there a case to be made for a resurgence?

As we bring this year to a close, markets continue to frustrate. The US markets, along with most global markets and especially Canada, are all negative. Over the past few weeks Canada has dipped as low as -13% on it’s year-to-date (YTD) return. In speaking with some people within my industry, expectations to finish flat for the year will be sufficient for a pat on the back and considered solid performance.

As we bring this year to a close, markets continue to frustrate. The US markets, along with most global markets and especially Canada, are all negative. Over the past few weeks Canada has dipped as low as -13% on it’s year-to-date (YTD) return. In speaking with some people within my industry, expectations to finish flat for the year will be sufficient for a pat on the back and considered solid performance.