In my head is the vague memory of some political talking head who predicted economic ruin under Obama. He had once worked for the US Government in the 80s and had predicted a recession using only three economic indicators. His call that a recession was imminent led to much derision and he was ultimately let go from his job, left presumably to wander the earth seeking out a second life as political commentator making outlandish claims. I forget his name and, so far, Google hasn’t been much help.

I bring this half-formed memory up because we live in a world that seems focused on ONE BIG THING. The ONE BIG THING is so big that it clouds out the wider picture, limiting conversation and making it hard to plan for the future. That ONE BIG THING is Trump’s trade war.

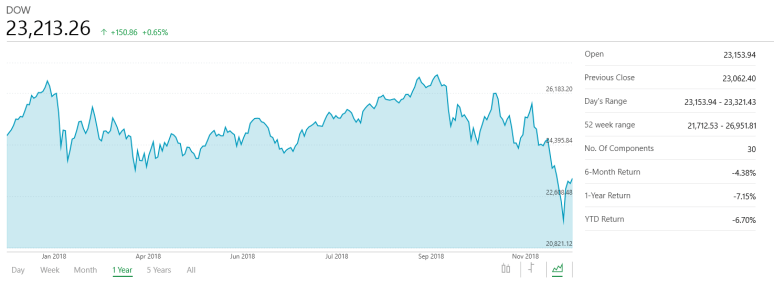

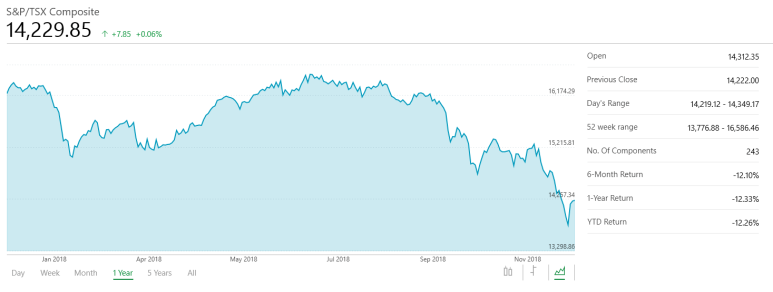

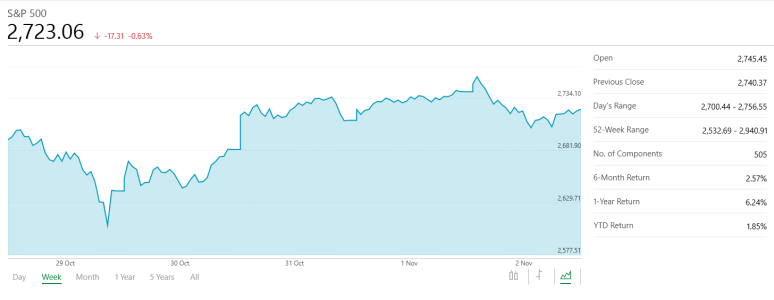

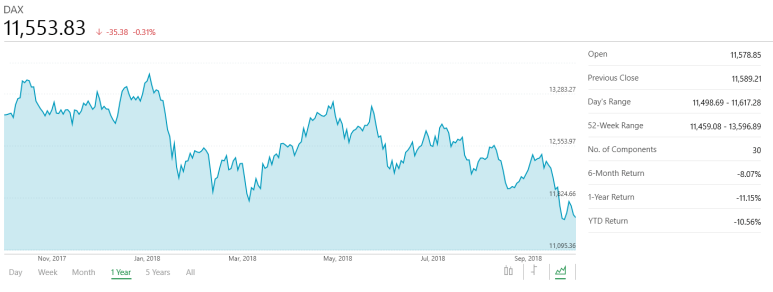

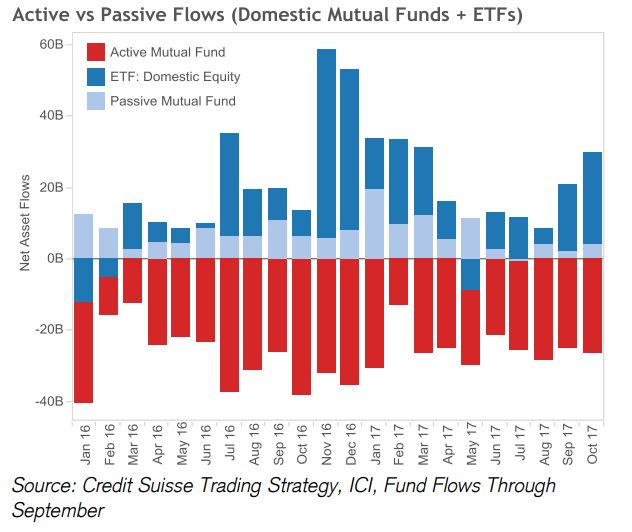

I get all kinds of financial reports sent to me, some better than others, and lately they’ve all started to share a common thread. In short, while they highlight the relative strength of the US markets, the softening of some global markets, and changes in monetary policy from various central banks they all conclude with the same caveat. That the trade war seems to matter more and things could get better or worse based on what actions Trump and Xi Jinping take in the immediate future.

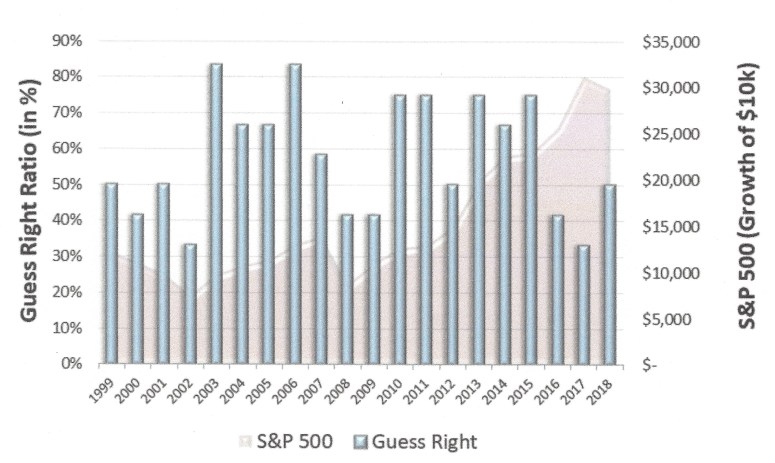

Now, I have a history of criticizing economists for making predictions that are rosier than they should be, that predictions tend towards being little more than guesses and that smart investors should be mindful of risks that they can’t afford. I think this situation is no different, and it is concerning how much one issue has become the “x-factor” in reading the markets, at the expense of literally everything else.

What this should mean for investors is two-fold. That analysts are increasingly making more useless predictions since “the x-factor” leaves analysts shrugging their shoulders, admitting that they can’t properly predict what’s coming because a tweet from the president could derail their models. The second is that as ONE BIG THING dominates the discussion investors increasingly feel threatened by it and myopic about it.

This may seem obvious, but being a smart investor is about distance and strategy. The more focused we become about a problem the more we can’t see anything but that problem. In the case of the trade war the conversation is increasingly one that dominates all conversation. And while the trade war represents a serious issue on the global stage, so too does Brexit, as does India’s occupation of Kashmir (more on that another day) , the imminent crackdown by the Chinese on Hong Kong (more on that another day), the declining number of liberal democracies and the fraying of the Liberal International order.

This may not feel like I’m painting a better picture here, but my point is that things are always going wrong. They are never not going wrong and that had we waited until there were only proverbial sunny days for our investing picnic, we’d never get out the door. What this means is not that you should ignore or be blasé about the various crises afflicting the world, but that they should be put into a better historical context: things are going wrong because things are always going wrong. If investing is a picnic, you shouldn’t ignore the rain, but bring an umbrella.

The trade war represents an issue that people can easily grasp and is close to home. Trump’s own brand of semi-authoritarian populism controls news cycles and demands attention. Its hard to “look away”. It demands our attention, and demands we respond in a dynamic way. But its dominance makes people feel that we are on the cusp of another great crash. The potential for things to be wiped out, for savings to be obliterated, for Trump to be the worst possible version of what he is. And so I caution readers and investors that as much as we find Trump’s antics unsettling and worrying, we should not let his brash twitter feuds panic us nor guide us. He is but one of many issues swirling around and its incumbent on us to look at the big picture and act accordingly. That we live in a complex world, that things are frequently going wrong and the most successful strategy is one that resists letting ONE BIG THING decide our actions. Don’t be like my half-remembered man, myopic and predicting gloom.

Information in this commentary is for informational purposes only and not meant to be personalized investment advice. The content has been prepared by Adrian Walker from sources believed to be accurate. The opinions expressed are of the author and do not necessarily represent those of ACPI.

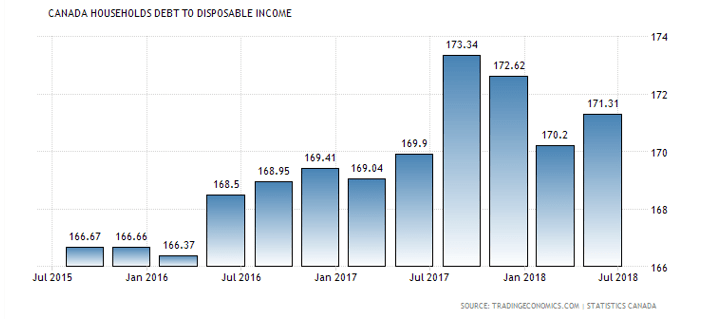

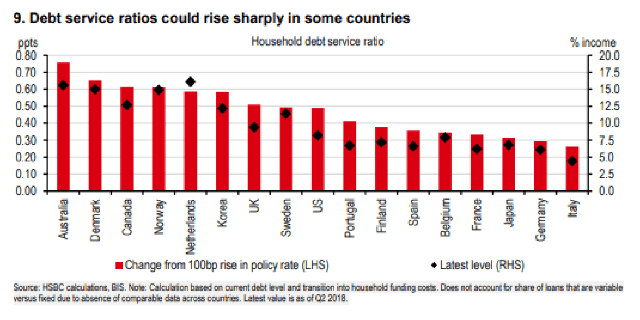

The temptation to assume that everything is about to go wrong is therefore not the most far-fetched possibility. Investors should be cautious because there are indeed warning signs that the economy is softening and after ten years of bull market returns, corrections and recessions are inevitable.

The temptation to assume that everything is about to go wrong is therefore not the most far-fetched possibility. Investors should be cautious because there are indeed warning signs that the economy is softening and after ten years of bull market returns, corrections and recessions are inevitable.

I wish to inform you about an exciting new profession, currently accepting applicants. Accurate recession prognostication and divination is an up and coming new business that is surging in these turbulent economic times! And now is your chance to get in on the ground floor of this amazing opportunity!

I wish to inform you about an exciting new profession, currently accepting applicants. Accurate recession prognostication and divination is an up and coming new business that is surging in these turbulent economic times! And now is your chance to get in on the ground floor of this amazing opportunity!