Donald Trump’s presidency is most generously described as a mixed bag. To his supporters he is the most accomplished president since Regan, maybe ever. To his detractors he is a dangerous demagogue whose flouting of democratic norms and curiously close connections to Russia (which predate his run for the presidency) threaten multiple constitutional crises. Undeniable is that his pursuit of electoral victory has meant that he’s been more than willing to entertain the support of racists and neo-nazis, and even his champions admit he seems oblivious to the importance of the traditional alliances that support the world order. Economists bemoan his understanding of economics, which seems especially dubious when it comes to international trade and tariffs. We’ve yet to discuss his own personal vulgarities.

Donald Trump’s presidency is most generously described as a mixed bag. To his supporters he is the most accomplished president since Regan, maybe ever. To his detractors he is a dangerous demagogue whose flouting of democratic norms and curiously close connections to Russia (which predate his run for the presidency) threaten multiple constitutional crises. Undeniable is that his pursuit of electoral victory has meant that he’s been more than willing to entertain the support of racists and neo-nazis, and even his champions admit he seems oblivious to the importance of the traditional alliances that support the world order. Economists bemoan his understanding of economics, which seems especially dubious when it comes to international trade and tariffs. We’ve yet to discuss his own personal vulgarities.

Having said all of this, we must address the paradox of Donald Trump, and that is his ability to pursue change, and find success on issues that are seemingly set in stone. His NAFTA talks, which have ended in a deal, have brought only minor concessions from Canada and Mexico. However it should be noted they are concessions slightly greater than previously negotiated under the TPP which the US declined to be part of. His chaotic approach to governing seems to endanger many of his own goals, and when he is stymied in his objectives he is typically the source of his own sorrows. But that doesn’t mean that he doesn’t have some method to his madness.

The world order that has existed since the end of the WW II, and which went into overdrive following the collapse of the Soviet Union, has succeeded in enriching the world in ways that might be considered unimaginable by previous generations. In 2018 more free nations exist, fewer people live in poverty while crime and war are at all time lows. This is all part of a trend known as the great convergence, the catching up of developing economies to developed ones and the benefits a post scarcity society brings. This change, which is helping wipe out extreme poverty and improve the lives of billions brings with it a global shift in power. Europe and the United States, though still the largest economies, are no longer alone on the world stage and the idea of a unipolar world is no longer viable. Regional powers are reasserting themselves and that includes China whose rise has been considered inevitable by most Western nations.

But China’s ascendance is coming with a high cost. China refuses to respect international rules around intellectual property; as an economic power it’s trade practices can destabilize markets; as an international power it is busy buying access to foreign countries with large scale infrastructure projects; as a military power it is in a belligerent fight to take control of the major trade routes through the South China Sea; and in the fields of espionage it is engaged (like Russia) in extensive cyber activities. Left unchecked China represents an opposite pole in the globe that (like Russia) promotes a global order that isn’t interested in law, international agreements and global norms, but aims instead towards regional autonomy free from such restrictions.

Whether Trump believes in the “global liberal order” isn’t clear, but he seems to see that America is involved in a fight with China, one that it may not have an opportunity to fight again under terms this favorable. This is part of the paradox of Donald Trump. As political theorist Ian Bremmer has pointed out, much of Trump’s insights are not bad but the way he puts them into practice undermines his own ambitions, and hurts the alliances that are needed to sustain his goals and the liberal order. Thus, he’s as likely to upset his allies as he is to rattle America’s foes. In this respect Trump is more similar to Vladimir Putin or Xi Jingpin, who see that national interests should supersede international ones (and where national interests never conflict with the leader’s interests).

Last week I wrote an article about how Canada could lose NAFTA, only to have a new deal come into place on Sunday. I scrapped that piece, but my view remains that Trump’s only sacred cow is his own instincts and that investors shouldn’t assume that that things will work out simply because there might be some political or popular resistance. The success of the status quo is not a guarantee that things will fall back into place and history reminds us that the assumption of inevitability is folly. Things can change, sometimes irrevocably so.

Donald Trump remains a paradox, a leader who touches on good ideas but is unsure how to implement them. The head of the free world who seems far more comfortable in the company of strong men and dictators. An anti-war candidate that may be in a Thucydidean trap with China. An elitist billionaire who seems to have better understood the frustrations of the common citizen. A self-described “great negotiator” whose skill nets only small gains. Investors, take note.

I recognize that writing about politics runs the risk of upsetting or offending readers. Some may regard criticism of a political person or view as an indirect criticism of themselves. This could not be farther from the truth, and we recognize that Trump would not be elected if he didn’t understand something true about the world. We write to help explain our world view and how we believe we should approach investing opportunities and risks. If you are curious about what has informed this view we recommend the following books:

- Enlightenment Now, Steve Pinker

- The Road to Unfreedom – Timothy Snyder

- The Clash of Civilizations – Samuel Huntington

- The Return of Marco Polo’s World – Robert Kaplan

- Every Nation for Itself – Ian Bremmer

- Homo Deus – Yuval Noah Harari

- China’s Great Wall of Debt – Dinny McMahon

- The Retreat of Western Liberalism – Edward Luce

- The Return of History – Jennifer Welsh

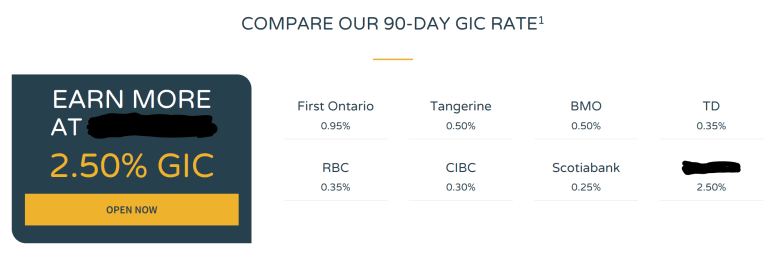

To say that Canadians aren’t financially literate may seem a touch unfair, but everywhere you look we find testaments to this unavoidable fact. Credit cards, car loans, mortgage rates and even how returns are calculated are a confusing mess for most people. The math that governs these relationships is often opaque and can feel misleading, and its complexity assures that even if some do understand it, the details will only be retained by a tiny minority.

To say that Canadians aren’t financially literate may seem a touch unfair, but everywhere you look we find testaments to this unavoidable fact. Credit cards, car loans, mortgage rates and even how returns are calculated are a confusing mess for most people. The math that governs these relationships is often opaque and can feel misleading, and its complexity assures that even if some do understand it, the details will only be retained by a tiny minority.

Armed with that info you might feel like the whole project makes sense. In reality, there are lots of questions about inflation that should concern every Canadian. Consider the associated chart from the American Enterprise Institute. Between 1996 – 2016 prices on things like TVs, Cellphones and household furniture all dropped in price. By comparison education, childcare, food, and housing all rose in price. In the case of education, the price was dramatic.

Armed with that info you might feel like the whole project makes sense. In reality, there are lots of questions about inflation that should concern every Canadian. Consider the associated chart from the American Enterprise Institute. Between 1996 – 2016 prices on things like TVs, Cellphones and household furniture all dropped in price. By comparison education, childcare, food, and housing all rose in price. In the case of education, the price was dramatic.

In Ontario the price of food is more expensive, gas is more expensive and houses (and now rents) are also fantastically more expensive. To say that inflation has been low is to miss a larger point about the direction of prices that matter in our daily lives. The essentials have gotten a lot more expensive. TVs, refrigerators and vacuum cleaners are all cheaper. This represents a misalignment between how the economy functions and how we live.

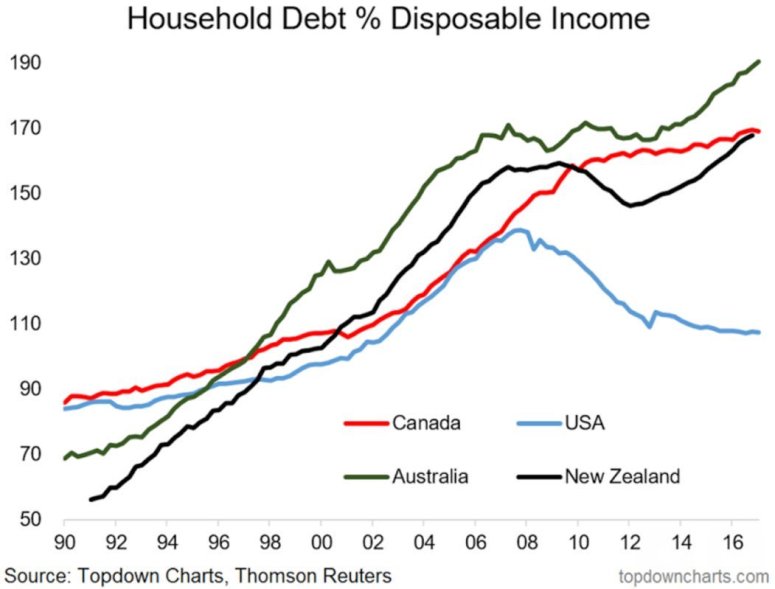

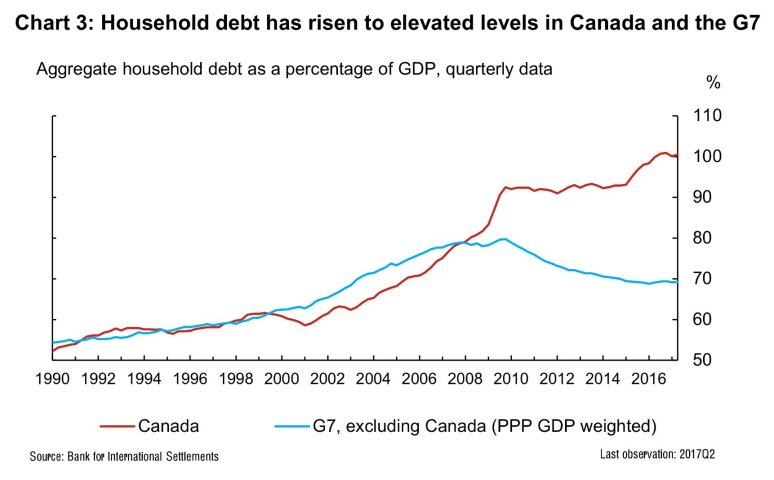

In Ontario the price of food is more expensive, gas is more expensive and houses (and now rents) are also fantastically more expensive. To say that inflation has been low is to miss a larger point about the direction of prices that matter in our daily lives. The essentials have gotten a lot more expensive. TVs, refrigerators and vacuum cleaners are all cheaper. This represents a misalignment between how the economy functions and how we live.  Economic data should be meaningful if it is to be counted as useful. A survey done by BMO Global Asset Management found that more and more Canadians were dipping into their RRSPs. The number one reason was for home buying at 27%, but 64% of respondents had used their RRSPs to pay for emergencies, for living expenses or to pay off debt. These numbers dovetail nicely with the growth in household debt, primarily revolving around mortgages and HELOCs, that make Canadians some of the most indebted people on the planet.

Economic data should be meaningful if it is to be counted as useful. A survey done by BMO Global Asset Management found that more and more Canadians were dipping into their RRSPs. The number one reason was for home buying at 27%, but 64% of respondents had used their RRSPs to pay for emergencies, for living expenses or to pay off debt. These numbers dovetail nicely with the growth in household debt, primarily revolving around mortgages and HELOCs, that make Canadians some of the most indebted people on the planet.

Self Driving Cars: In reality you aren’t likely to come across too many investments in this space. I’ve seen some through venture capitalists, but as a growing field and surrounded with lots of hype there is every reason to believe that firms will increasingly be looking for investors outside the venture capital space.

Self Driving Cars: In reality you aren’t likely to come across too many investments in this space. I’ve seen some through venture capitalists, but as a growing field and surrounded with lots of hype there is every reason to believe that firms will increasingly be looking for investors outside the venture capital space. This kind of regulatory uncertainty should give investors real pause when they consider which companies to invest in. Most marijuana growers have no profits and only debt and are betting on big returns once markets open up. They would not be the first companies to badly misread what the future holds.

This kind of regulatory uncertainty should give investors real pause when they consider which companies to invest in. Most marijuana growers have no profits and only debt and are betting on big returns once markets open up. They would not be the first companies to badly misread what the future holds. Currencies that are subject to incredible volatility are not normally appealing to investors. In fact stability is the key for most currencies, and the Bitcoin phenomena should not be an exception to this. Bitcoin’s intellectual champions point out that it is a versatile currency and a store of value, but if you were a retailer how would you feel accepting payment from a currency that can drop 30% in one day? As a consumer it also would trouble you to pay $5 worth of bitcoins one day only to find out it was worth 1000% more a month later. Currencies work because people will readily part with it for other goods confident that the value is roughly consistent over time.

Currencies that are subject to incredible volatility are not normally appealing to investors. In fact stability is the key for most currencies, and the Bitcoin phenomena should not be an exception to this. Bitcoin’s intellectual champions point out that it is a versatile currency and a store of value, but if you were a retailer how would you feel accepting payment from a currency that can drop 30% in one day? As a consumer it also would trouble you to pay $5 worth of bitcoins one day only to find out it was worth 1000% more a month later. Currencies work because people will readily part with it for other goods confident that the value is roughly consistent over time.

In his excellent book

In his excellent book

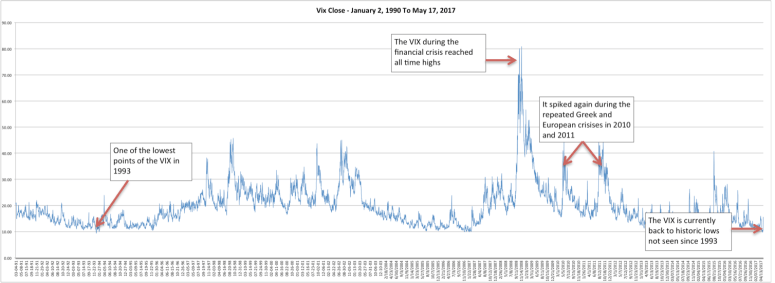

On the other hand chronic instability has a way of building in systems. One of the reasons that serious conflicts, political instability and angry populism haven’t done much to negate market optimism is because the nature of Western Liberal democracies is to be able to absorb a surprising amount of negative events. Our institutions and financial systems have been built (and re-built) precisely to be resilient and not fragile. Where as in the past bad news might have shut down lending practices or hamstrung the economy, we have endeavored to make our systems flexible and allow for our economies to continue even under difficult circumstances.

On the other hand chronic instability has a way of building in systems. One of the reasons that serious conflicts, political instability and angry populism haven’t done much to negate market optimism is because the nature of Western Liberal democracies is to be able to absorb a surprising amount of negative events. Our institutions and financial systems have been built (and re-built) precisely to be resilient and not fragile. Where as in the past bad news might have shut down lending practices or hamstrung the economy, we have endeavored to make our systems flexible and allow for our economies to continue even under difficult circumstances.

Some time ago I wrote that it really didn’t matter

Some time ago I wrote that it really didn’t matter