Is America’s economy failing? Has Trump undone the American economic empire? Do ports sit empty? Are people being laid off? Have world leaders conspired to control America’s debt?

These are just some of the headlines and subjects floating around the internet. Depending on who you are and where your political allegiances lay, the answers will be self-evident. Trump is either a an economic genius and unparalleled negotiator, or he is a clumsy and indifferent conman masquerading as successful businessman and politician.

For investors this presents a real challenge. These questions aren’t just thought experiments. Depending on the answers they may significantly impact where one chooses to invest, and the more polemical the question the farther we may get from a useful answer, regardless of politics. If our goal is to ask questions to reveal truth, we may find ourselves confused as to why markets have surged back from their lows (as of May 12th the major US indices have almost recovered from their tumble at the beginning of April) even while business reporting warns of a potential for a worsening economy.

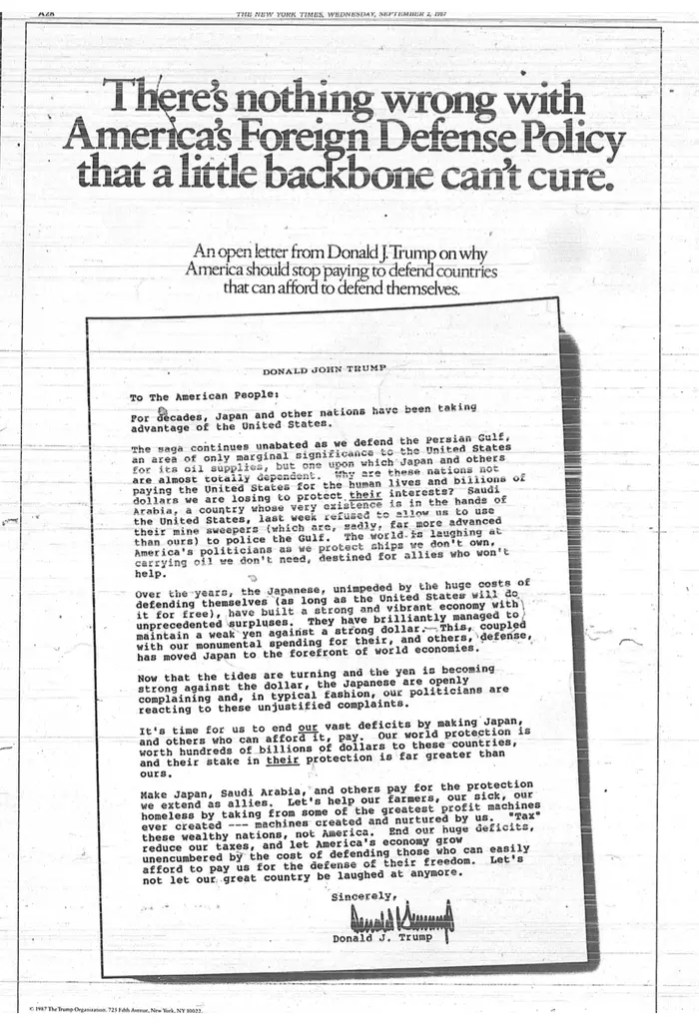

One way to make better sense of what’s happening is to put ourselves in the shoes of Donald Trump’s administrative allies. Imagine what someone who believes in what Donald Trump is doing would say about his economic plans. Its not as though they haven’t heard economists and businesses express doubt and worry about the actions of his administration. So how would they defend them?

In my imagining I believe they would argue something like the following:

The United States is enormously rich but wastes money on cheap goods from China, and while some of these goods don’t need to be made here, America has lost enough manufacturing jobs that its worthwhile experimenting with tariffs to bring jobs back. Over the past 45 years we’ve seen countless evidence that playing by the rules of globalization reduces the ability of governments to help their most vulnerable citizens, and money has become too fluid and too willing to cross borders at the expense of their domestic homes. Regardless of what people fear, America remains the richest country in the world, with the largest consumer base, and that combined with the existing strength of the US economy will be enough to bring industry back to the US in some capacity while tariffs on junk from other countries will help pay for renewed and permanent tax cuts. Market volatility will be temporary while the economy realigns itself, but the combination of lower taxes and existing economic strength will ultimately help lift the markets even higher.

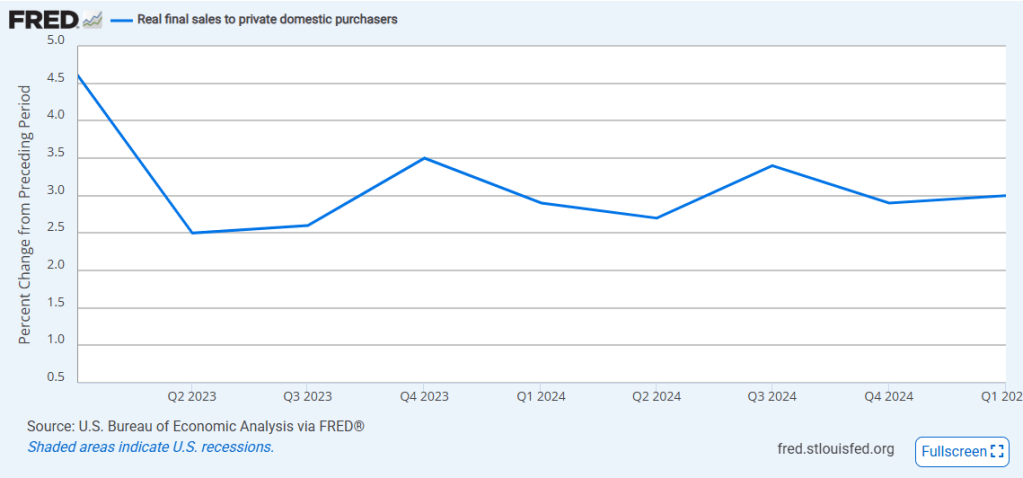

You don’t have to believe in such a claim, or even pretend this was what Donald Trump campaigned on. What I’m putting forth is a set of ideas (picked up through numerous interviews and speeches) that I believe his administration finds largely defensible and recognizable, and would be a better frame of reference for understanding their actions. Let’s start with the recent indication that GDP is contracting. In traditional economic terms, two quarters of back-to-back GDP contractions constitute a recession. We’ve had more than a few of those over the past decade, but few people would say that we’ve had recessions. The reason for this might be best expressed by Jason Furman; an American economist, professor at Harvard, and former deputy director of the US National Economic Council, in a recent editorial in the Financial Times. Outlining the importance of “Core GDP” vs “GDP”, he points out that Core GDP (actually known as Real Final Sales to Private Domestic Purchasers) better reflects consumer spending and private investment while the traditional GDP includes net exports, inventories, and government spending, all things in flux because of Trump’s new administration. So, while the GDP contracted in Q1 of this year, the Core GDP was up in the first three months.

What about rumours of empty ports and empty shelves? Reportedly Trump was shaken following meetings with the heads of three major retailers about shelves being empty if the tariff’s remain at 145% on China. Trump seems to have vacillated a number of times about the size and implementation of the tariffs, but as of today they remain intact. Asked about higher prices and fewer options Trump seemed dismissive of concerns over the Chinese trade war declaring “maybe the children will have two dolls instead of thirty dolls, and maybe those dolls will cost a couple of bucks more.”

Is Trump being dismissive? Yes, but he’s also not worried that shelves will be empty. Though shipping and imports are down as we head into May for cargo coming from China, far from alarmist rumours that docks are sitting empty there is still plenty of ocean-going traffic coming from China.

Does this mean that there won’t be furloughed dock workers or empty shelves? According to the Port of Los Angeles there has been a 35% drop week over week of expected cargo, and a 14% decline from the previous year. That very well may lead to reduced working hours and fewer options in stores, but the discrepancy between what’s being shared online and what is likely to actually happen is probably enough to gird the loins for Trump’s team to continue their policies.

What about layoffs? Fears about unemployment remain high, but as the most recent jobs report shows hiring remains robust and the unemployment rate, already very low, remains unchanged.

This discrepancy between a popular public impression and the on-the-ground economic reality gives room to Trump’s administration to continue ahead with ideas that remain controversial, as well as opening up investors to making mistakes in their allocations. For the time being, Trump does have a reservoir of economic and political strength to call on. He may be using that reserve up, but may also have guessed with some accuracy that the global economy will keep doing business with America regardless of whatever feathers he ruffles.

But markets may also not be calculating the longer-term direction correctly, mispricing assets and remaining too optimistic. Since Trump’s re-election markets have been shown to be placated by the promise of deferred tariffs, as though deferring them is really the prelude of getting rid of them. Trump doesn’t help this by going back and forth on their implementation, but listening to his words, and following his actions, I feel that it would be a mistake to assume that the tariffs will ultimately be rescinded.

This past week changes to the auto-tariffs were announced, reducing some of the duplication of tariffs on steel and aluminum, but also laid out reimbursements and tariff relief for parts manufacturers need to import. These changes also make clear the groundwork for a longer and more durable tariff regime. Trump himself has been quick to correct any reporting that suggests that he’s backtracking or creating exemptions for specific products, and that some products may end up with different tariff treatment, but will still be subject to tariffs.

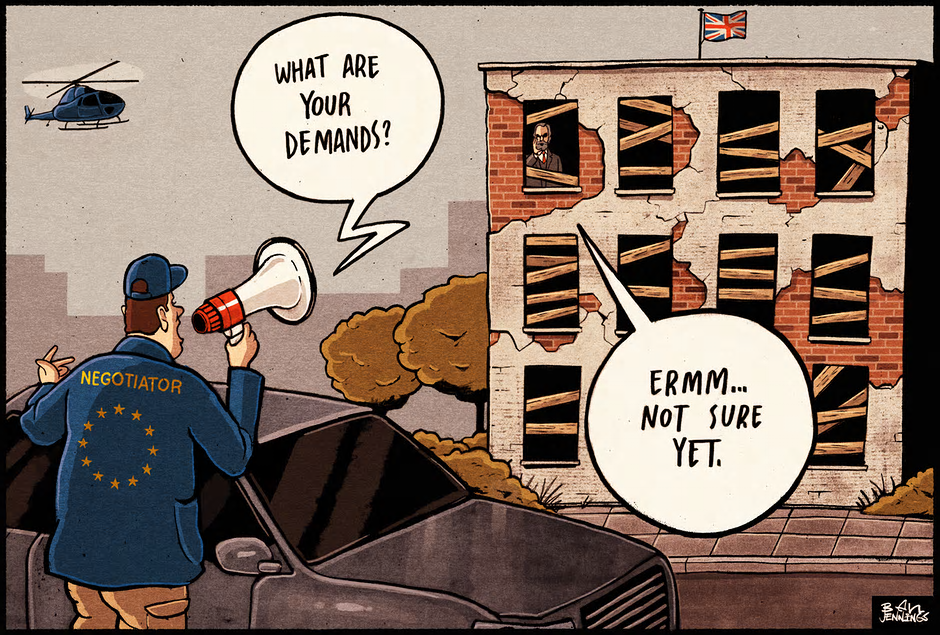

This seems best exemplified by the announcement of the US-UK trade deal. Called “a starting point” by the British ambassador, the Trump administration has said the deal is “maxed out”, leaving in place a 10% tariff on British imports, with a reduced tariff on British cars, steel, and aluminum (the deal effectively lowers car and steel duties to the flat 10% rates, down from 27.5%).

Whether deals such as these are anything for the market to get excited about is a question that will be answered with time, like all the unanswered questions that have been introduced this year. What investors must work on is remaining clear eyed about what is happening, and resist submitting to their own partisan preferences. Trump may yet undermine the US economy, and trade deals may turn out to simply be acknowledgements of existing tariff rates, or perhaps the opposite may happen. But recognizing that reality is more mixed and that we do not yet have a clear picture about the future will promote more time tested strategies for sensible investing.

Aligned Capital Partners Inc. (“ACPI”) is a full-service investment dealer and a member of the Canadian Investor Protection Fund (“CIPF”) and the Canadian Investment Regulatory Organization (“CIRO”). Investment services are provided through Walker Wealth Management, an approved trade name of ACPI. Only investment-related products and services are offered through ACPI/Walker Wealth Management and covered by the CIPF. Financial planning services are provided through Walker Wealth Management. Walker Wealth Management is an independent company separate and distinct from ACPI/Walker Wealth Management.

On the other hand chronic instability has a way of building in systems. One of the reasons that serious conflicts, political instability and angry populism haven’t done much to negate market optimism is because the nature of Western Liberal democracies is to be able to absorb a surprising amount of negative events. Our institutions and financial systems have been built (and re-built) precisely to be resilient and not fragile. Where as in the past bad news might have shut down lending practices or hamstrung the economy, we have endeavored to make our systems flexible and allow for our economies to continue even under difficult circumstances.

On the other hand chronic instability has a way of building in systems. One of the reasons that serious conflicts, political instability and angry populism haven’t done much to negate market optimism is because the nature of Western Liberal democracies is to be able to absorb a surprising amount of negative events. Our institutions and financial systems have been built (and re-built) precisely to be resilient and not fragile. Where as in the past bad news might have shut down lending practices or hamstrung the economy, we have endeavored to make our systems flexible and allow for our economies to continue even under difficult circumstances.

2017 will begin to rectify some of these issues. Next week we will see the arrival of President Donald Twitterbot™, finally ending speculation about what kind of president Donald Trump will be and seeing what he actually does. So far markets have been reasonably calm in the face of the enormous uncertainty that Trump represents, but his pro-business posture seems to have got traders eager for a more unregulated market with greater earnings for the future. Right now bets are that Trump might really jump start the economy, but there are real questions as to what that might mean. Unemployment is already very low and inflation looks like it is actually beginning to creep up.

2017 will begin to rectify some of these issues. Next week we will see the arrival of President Donald Twitterbot™, finally ending speculation about what kind of president Donald Trump will be and seeing what he actually does. So far markets have been reasonably calm in the face of the enormous uncertainty that Trump represents, but his pro-business posture seems to have got traders eager for a more unregulated market with greater earnings for the future. Right now bets are that Trump might really jump start the economy, but there are real questions as to what that might mean. Unemployment is already very low and inflation looks like it is actually beginning to creep up.