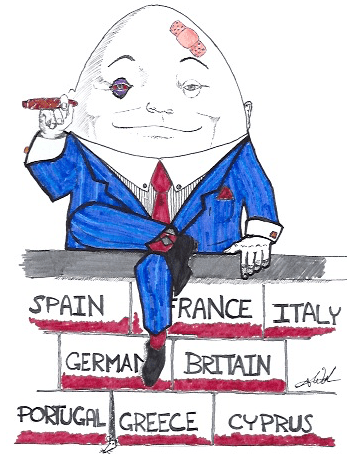

It’s been a tough few years for the Eurozone. Between the ongoing debt problems and the pervasive deflation Europe has seemed to be on the ropes consistently since 2008. Somehow the Union has continued to survive, despite being constantly assailed by financial crises, rejected constitutions and now referendums on future membership.

What all these problems represent is the failed integration of the European people into a “European people”. Despite years of effort Germans are still Germans, French are still French, and Brits are still Brits. In fact, far from creating an integrated whole where a common identity is shared across the continent, many countries face challenges about their own integrity. The Scottish nearly became a country separate from Great Britain, in Spain a Catalonian independence party recently won big, and don’t get me started on the issue in Belgium. What this all means is that national self interest still trumps European self interest, and so while Greek problems affect everyone they remain primarily Greece’s problems in the eyes of many.

Meanwhile interest in being part of the EU is on the wane, with Britain scheduled to have a referendum on its future involvement leading a general trend about Euroscepticism. In Holland a whopping 83% of voters want greater say about transfers of power to the EU. On December 3rd, Denmark will be voting about changing its “opt-out” status into “opt-in”, but the anti-euro sentiment is growing and while a pro-EU yes side seems to be winning, it isn’t winning by much.

Other countries that had sidestepped EU membership are decidedly more firm about not joining. Norway’s initial membership was ultimately rejected by a small majority in the 1970s, today pro-EU support in Norway is only around 20%. In Iceland, a country that has had a pending request to join the Union for some years let its membership request lapse this year, citing that its future is better served outside the EU.

Into this mess is the migrant crisis, which while currently focused on the Syrian refugee situation has been a much longer issue including the abundant number of people risking life and limb crossing the Mediterranean from North Africa. But despite how moving the plight of the refugees has been, including the sad picture of a little boy drowned on a beach in Turkey, the German response of “no upper limit” for refugees seems to have already hit it’s upper limit. The President of Germany, Joachim Gauck, has said “Our reception capacity is limited even when it has not yet been worked out where limits lie,” a sentiment that has been echoed by other German politicians and an increasing number of Germans themselves.

With 10,000 refugees arriving daily into Germany and still boatloads more coming into the south coast, Europe is finding itself stretched to the limits about how to deal with such an influx of migrants. The scale of the human suffering that is prompting these moves makes it often impolite to discuss the nuts and bolts of taking so many people at one time, and objections raised by critics are quickly shouted down as racist. But with more than 800,000 refugees this year expected by Germany there are calls to fairly distribute the asylum seekers across Europe, a call meeting mixed to negative responses by many nations.

Much of the focus on Europe’s woes has been about financial matters, but the EU has aimed to be more than a financial union, it has sought a social union as well. And while Europe’s financial problems are well understood and the response to those problems have been unified, the social integration is far from even. Germany may have taken a stand for enlightened moral behavior in accepting so many people, but they notably don’t speak for many other nations, neither rich like Britain (a promise of 20,000 over the next five years) or poor like Greece who had 50,000 people arrive in July alone.

And despite whatever successes the EU bestows upon member states, a future European Union may be a looser European Union in the end, in itself a promise of more instability for the future of Europe.