When Jane Jacobs died in 2006, her Annex home sold for a reported $3,000,000. A lofty sum, but a fitting metaphor for the career of a woman so central to how we’ve come to understand cities and urban growth.

Cities, almost everywhere, are under a crunch to meet the needs of growing populations and affordable housing. In Canada two cities stand out as being places to go when you are looking for work, Toronto and Vancouver, and notably they have both been beset with rapidly inflating housing prices. And while I have covered this topic many times (many, many, many times), recently various governments have seen fit to try and wrestle the housing monster to the ground before it explodes and does long term damage to the economy.

First, a BC law was passed on foreign buyers. Totalling 15%, early signs are that it has worked in Vancouver and Victoria. Sort of. In late October several news outlets published the startling result that “Home Sales Plunge 38.8%”, which is helpfully misleading. The gross number of home sales on a year over year result (that is October 2015 vs October 2016) was 61.2% of what it had been in the previous year. 3646 homes were sold in October 2015, and 2233 were sold in October 2016. A corresponding decline in price for the same two periods was non-existent. Prices were actually up year over year, by 24.8%, though the average price had dropped by 0.8% from September.

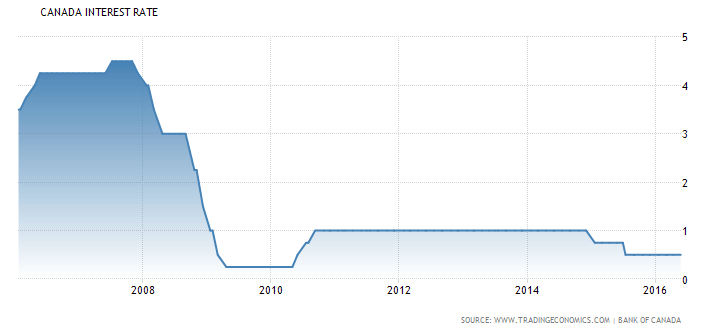

The next set of laws has come from the federal government, which is trying to improve the financial health of those seeking mortgages by setting higher thresholds for banks and CMHC insurance qualifications. More recently imposed than the BC foreign buyers tax, we’ve yet to see what kind of impact these new rules will have, but I’m willing to posit a guess.

Like the BC law, the new national rules will do more to curtail the supply of property than it will reduce price and limit demand. The reason for this is that governments are attempting to tackle the part of the housing problem they feel most comfortable in, taxing and regulation. And while we know fundamentally very little about how many foreign buyers there are and what impact they are having on the Canadian market (among other obtuse aspects of Canadian realty, you can read about these issues here.), regulation and taxation are well understood tools that most politicians feel comfortable using even when the problem may still not be well understood.

What governments are loath to do though is tackle the part of the problem they could have the greatest impact on, which is supply. Governments, municipal and provincial, have a big say in what can get built and at what speed. But cities like Toronto frequently challenge their own growth, trying to straddle the boundary between their future needs while obsessively preserving some idea of a perfect version of itself.

The efforts the city and province have made, to try and “densify” urban corridors while leaving the neighbourhoods of detached homes in between them untouched, is probably failing in some measure. First because the neighbourhoods themselves aren’t super excited about 20 story buildings going up within the line of sight of their homes. Second because many people don’t see themselves raising families in condos, leading to an abundance of 500 – 700 sq-ft spaces that only serve first time buyers, but not growing families.

The resistance that neighbourhoods put up to growth can be almost comical. From petitions to “Stop Density Creep” to city councilors objecting to condos not being “in keeping with the community” in our most urbanly dense sectors, citizens and their representatives can be almost hysterically opposed to any changes that might affect them.

And so we come back to Jane Jacobs. There is unlikely anyone more influential on how we think of cities than Jane Jacobs. She’s responsible for many great ideas about livable spaces, about how sidewalks and cities need people to thrive, the benefits of cities for bringing different people from different socio-economic backgrounds together and the importance of making cities for people, and not cars. When she lived in New York she fought against the likes of Robert Moses, and the push for more highways (frequently built at the expense of poorer neighbourhoods). When she brought her family to Toronto to avoid the Vietnam war (her kids were of drafting age) she moved into the Annex and fought against plans for the Spading Expressway (now Allan Rd) and campaigned so that its southern portion was never built.

And so we come back to Jane Jacobs. There is unlikely anyone more influential on how we think of cities than Jane Jacobs. She’s responsible for many great ideas about livable spaces, about how sidewalks and cities need people to thrive, the benefits of cities for bringing different people from different socio-economic backgrounds together and the importance of making cities for people, and not cars. When she lived in New York she fought against the likes of Robert Moses, and the push for more highways (frequently built at the expense of poorer neighbourhoods). When she brought her family to Toronto to avoid the Vietnam war (her kids were of drafting age) she moved into the Annex and fought against plans for the Spading Expressway (now Allan Rd) and campaigned so that its southern portion was never built.

But Jacob’s legacy has born some strange fruit. Though Jacob’s herself did seem to support growth of cities and solid development, the movement she helped birth and guide has become paranoid, myopic and NIMBY-istic. Here in Toronto we both benefit from her insight, and are hobbled by it as well. We have learned to love cities as places for people, but have grown suspicious of the development needed to accommodate our growth.

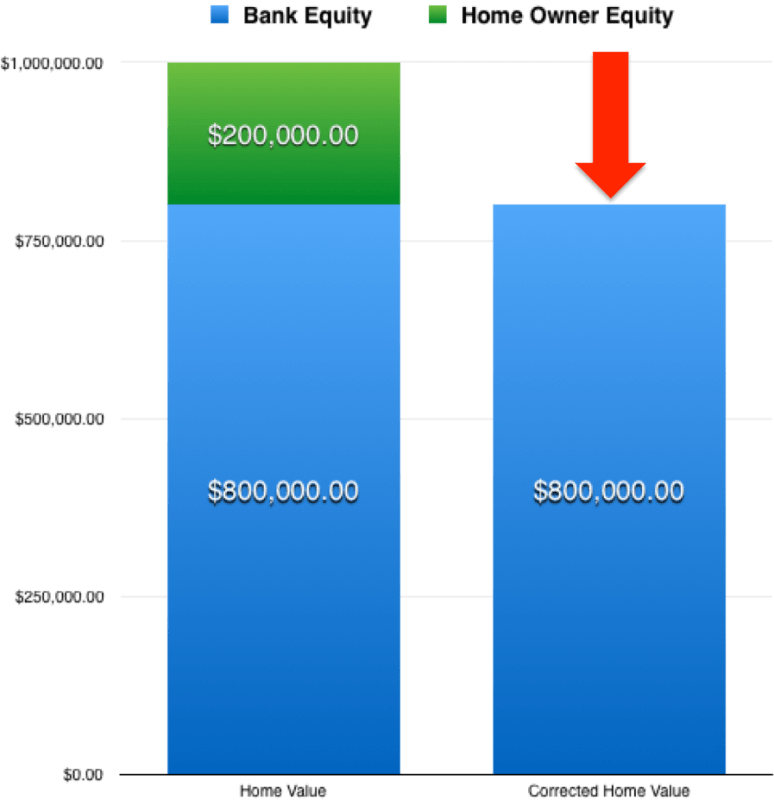

Against those challenges, stricter regulations for new home buyers and a tax on foreigners seems to do very little to solve the one problem we do have, not enough supply. While tightening the lending restrictions is important to stemming the growing debt burden saddled on Canadians, the goal should still be to restore a healthy real estate market to our major cities, both a certain way to avert a massive housing bubble implosion and a way of making homes more affordable. That seems to be a challenge our elected officials aren’t up to yet.