Supporters of President Donald Trump rally at the U.S. Capitol on Wednesday, Jan. 6, 2021, in Washington. THE CANADIAN PRESS/AP, Jose Luis Magana

The shocking scenes of Trump supporters storming the capitol building on January 6th, sometimes jovially, other times with what seemed like murderous intent, may have permanently cemented Trump’s fate. He’s been impeached, again, and efforts are being made to prevent him from running for office in the future. He may also be facing multiple criminal charges and possibly even bankruptcy.

Explanations for the insurrection both over and under explain the problem. Yes, Trump is a demagogue and its true his supporters have been radicalized in a number of ways, including conspiratorial thinking and racist ideas about threats to white people and black lives matter. But as the saying goes, “the issue isn’t the issue”.

In a video about anti-vaxxers (people who promote ideas that are untrue about vaccines) the YouTube Channel WiseCrack pointed out that vaccine acceptance was highest during and just after the Second World War, a period of high confidence and trust in the government by the American citizenry. Today that confidence has ebbed to an all-time low, and that collapse in trust isn’t necessarily unwarranted. The rise of a managerial and technocratic elite has placed an unacceptable distance between citizens and their governments, while government failures seem never to lead to any improvements or accountability.

The cost of these mistakes remains high. In Europe it has led to Brexit, months of protests by “Yellow Vests” in France, the erosion of the center-left ruling party in Germany and a resurgent far right party, the decline of liberal democracies in Hungary and Poland, and a number of anti-establishment parties getting control of small countries like Greece and big countries like Italy.

Canada, forever looking reasonable and calm compared to other countries, is having its own struggles. Prior to the pandemic we had rail protests across the country, have shown a consistent inability to get large infrastructure built and continue to see the erosion of our manufacturing sector. Pandemic response itself has been a laughable mess, from overconfident and condescending pronouncements on the ineffectiveness of masks and accusations of racism about concern of the virus, to complete reversals of position. Vaccine acquisition and distribution has also been underwhelming. The federal government didn’t seem to get enough at the right time, and provincial governments have struggled to get the vaccine to those who most need it (This is nothing compared to the US, where health care workers are actually refusing the vaccine).

In this moment, China can make credible claims for being a useful alternative to the US and other Western countries in its growing sphere of influence. A competent dictatorship with substantial economic growth and a rising standard of living must seem appealing to autocrats and some global citizens alike.

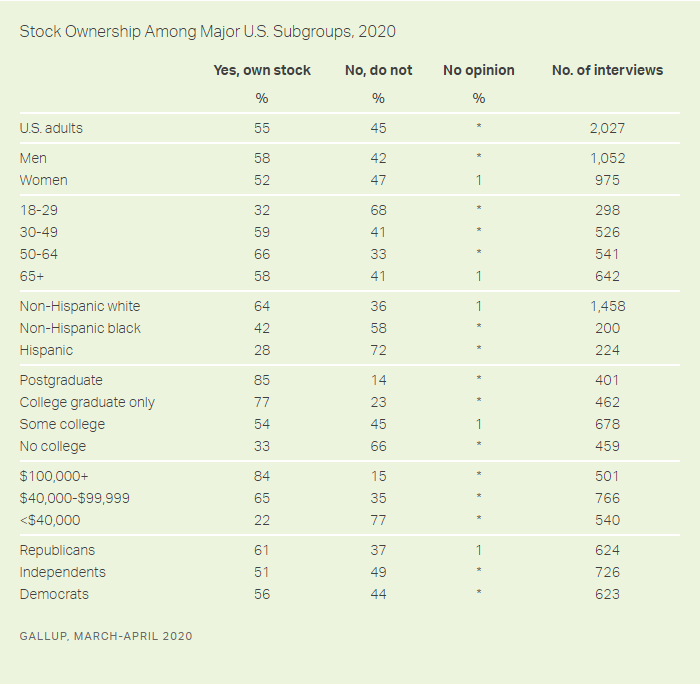

There are other concerns too. The gap between Main Street and Wall Street has grown ever wider. During early months of the pandemic the collapse of jobs and business was mirrored by a resurgent stock market that began gaining steam even while the real economy was crashing. This disparity between the world of investing and the world we live in only heightens inequality concerns. Ownership of stock by Americans closely correlates with age, ethnicity, wealth, and education. For many people today, inequality continues to look like a political class consorting with a billionaire class that don’t play by the same rules that govern everyone else. In a pandemic Jeff Bezos gets rich, and you get fired.

This is obviously not universal. Different countries have different problems and the degree to which these issues are felt by individuals depends a great deal on background and government. But even if we assume that the American situation represents an extreme amongst Western nations, it should not blind us to the anger that people rightly felt when they learned of politicians and executives travelling outside of Canada while asking everyone else to cancel their Christmas dinners. Politicians of all stripes seemed to believe that they would be exempt from the restrictions they imposed on others and had a hard time fathoming that constituents would be upset.

Fixing these problems will not be easy. Technocrats, that is governing authority due to technical expertise, imbues our current leaders with a lot of confidence on issues where there may be no correct answers. They leave people blind to what they do not know and encourage authorities to rely on models and projections rather than real life.

Take for instance inflation. Governments and central banks are very concerned with inflation. Too little and the economy will not grow. Too much and the economy will stall while savings lose value. Inflation needs to be “just right” which is currently considered somewhere between 1% – 3%, with a target rate of 2%. According to Statistics Canada, the CPI since 2010 has been around 1.5%, just below the current 2% target. In other words, $100 in 2010 would buy roughly $85 of similar goods today.

But would it?

Inflation has been higher and felt more directly by lower income people. Using data collected by Statistics Canada (you can click the link below to download the spreadsheet with all these numbers and my calculations) for retail food prices between November 2010 to November 2020, we can see that many food staples have become more expensive in the last decade at rates in excess of core inflation. In that time, the price of beef has risen between 4% to 7% per year depending on the cut. Potatoes have risen in price over 10%, onions by 5.5% and carrots by 6.3% a year. Baby food rose by an average of more than 9% a year, and toothpaste by 8%. Almost none of the staple groceries tracked by Statistics Canada had price increases contained to the 1.5% official rate of inflation, instead many rose at rates double that or more.

Like real estate, another asset class that continues to defy gravity without an impact on inflation but a dramatic one on the population, a rising price of food that remains unaddressed only highlights the different reality Canadians seem to be living from our elected officials. Despite a great deal of lip service about the importance and risks facing the middle class, governments have yet to seriously tackle these issues, or make them central in elections. Instead we continue to deal with these problems in a patchwork of modest tax credits and empty rhetoric.

I, and I assume many others, would like to put the Trump era behind us and treat it as an anomaly. But to do so would assume that Trump had landed (as had Brexit and other populist movements) fully formed but alien to us, and that we had been taken by a madness that can finally be broken.

I think we know this is not true.

From the moment that Hillary Clinton called Trump supporters “Deplorables” (or half of them at least) there has not been a clearer delineation between those that control the cultural zeitgeist, and those who have come to resent it. We have a similar divide in Canada too, with Alberta constantly at odds with more “progressive” provinces over environmental issues, and Quebec (doing as it always has) putting its historic/cultural/religious identity ahead of more multi-cultural aspirations of equality. Toronto and Vancouver may sit at the centre of Canada’s cultural output, but these two economic powerhouses do not share much with the rest of the country.

Our prolonged period of peace, wealth and stability has tricked us into believing that unrest, dissatisfaction, and failure are aberrations. But the history of Canada, the United States, Great Britain, and other European powers has been one of long periods of unrest. William Jennings Bryan, before being disgraced in the Scopes Money trial, had been a tireless campaigner for agrarian populism. In Canada we too had an agrarian populist movement (interestingly enough, similarly conservative and steeped in conspiratorial anti-Semitism, prominent in Alberta and Quebec) that only really started to disappear after the mid-60s and not totally until the late 80s. Political dissatisfaction can have long legs.

Five people died as a result of the assault on the capitol on January 6th, and one was Ashley Babbitt, a Q-Anon, MAGA loving Trump supporter who had breached four lines of security in an attempt to overthrow the government on behalf of Donald Trump. But while her motives and goals were deeply misguided, her past remains a window into a dispiriting world for many Americans. A fourteen year veteran of the United States air force, Babbitt now owned a pool supply business that was struggling, forcing her into a short term loan with a 169% interest rate. Medieval Europe had better rules governing usury than California. Or consider the North Carolina woman who took to social media because she couldn’t afford the $1000 insulin prescription for her son. Insulin, among other drugs in the United States, has been reported on multiple times for its rising price. Despite that, no government or corporation has been able to act in such a way to curb the rising price of a life saving drug that been around for a century.

All this is baked into America, and represents a growing risk for the future. Though the country has a more dynamic market, holds more patents and has some of the largest corporations, the failure to consider the effects of pushing up stock valuations at the expense of everything else will likely only deliver diminishing results in the future, both for investors like you, but also for the global liberal order that provides much of the stability we rely on.

Information in this commentary is for informational purposes only and not meant to be personalized investment advice. The content has been prepared by Adrian Walker from sources believed to be accurate. The opinions expressed are of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Aligned Capital Partners Inc.