In his book Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Taleb says of hindsight bias “A mistake is not something to be determined after the fact, but in the light of the information until that point.” With this guidance we can forgive some of the covid precautions and restrictions governments imposed on populations in 2020, a period of great uncertainty.

But in mid-2022 assessing the course of action by governments and central banks as they attempt to tackle a number of non-pandemic related crises (as well as still managing a pandemic that is increasingly endemic) I think its fair to say that mistakes are being made. From political unrest, to cost of living nightmares and finally inflation dangers, the path being plotted for us should be inviting closer scrutiny by citizens before we find ourselves with ever worsening problems.

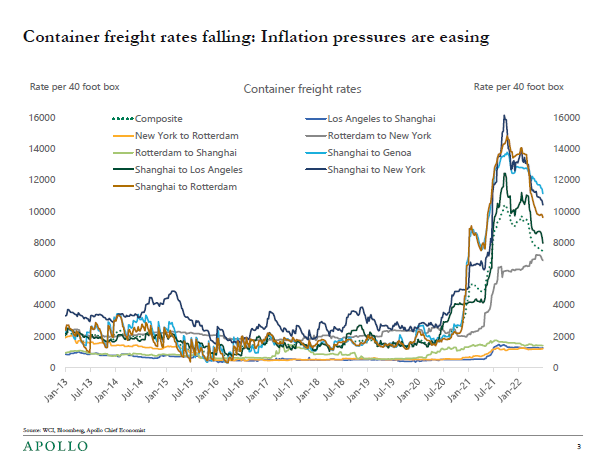

Let’s start with the twin risks of inflation and interest rates. Inflation is high, higher than its been in decades, and central banks the world over are attempting to stamp this out with aggressive rate hiking. It is easy to point to Turkey, a country whose inflation rate is 70%, and see that their recent cutting of interest rates is a mistake in the face of such crippling inflation. But what are we to make of North American efforts to slow inflation, even at the risk of a recession? Inflation for much of the West has been tied to economic stimulus (in the form of government action through the pandemic), supply chain disruptions and low oil and gas inventories. The economy is running “hot”, with lots of businesses struggling to find employees. But inflation, measured as the CPI is a rear-view mirror way of understanding the economy, also known as a lagging indicator. But here is one that is not. The price of container freight rates, which have fallen substantially from the 2021 highs.

We can count other numbers here too. The stock market, which is having a bad year, has fallen close to pre-pandemic highs. A $10,000 investment in the TSX Composite Index would have a return of 6.1% over the past 28 months, or an annualized rate of 2.6%. In February of this year that annualized rate was 8.85%, a 70% decline in returns. The numbers are worse for US markets. While US markets have performed better through the pandemic, the decline in the S&P500 is roughly 75% from its pandemic high in annualized returns (these numbers were calculated at the end of June, offering a recent low point in performance).

For many who felt that the stock market was too difficult to navigate but the crypto market offered just the right mix of “can’t fail” and “new thing”, 2022 has wiped out $2 trillion (yes, with a “T”) of value.

In fact speculative bubbles are themselves inflationary and their elimination will also help reduce inflation. Writes Charles Mackay in his famous book Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841) on the Mississippi Bubble in France, “[John] Law was now at the zenith of his prosperity, and the people were rapidly approaching the zenith of their infatuation. The highest and lowest classes were alike filled with a vision of boundless wealth…”

“It was remarkable at this time, that Paris had never before been so full of objects of elegance and luxury. Statues, pictures, and tapestries were imported in great quantities from foreign countries, and found a ready market. All those pretty trifles in the way of furniture and ornament which the French excel in manufacturing were no longer the exclusive play-things of the aristocracy, but were to be found in abundance in the houses of traders and the middle classes in general.”

Evidence today indicates that supply chains are beginning to correct, an important component of taming inflation, while trillions of dollars have been wiped out of a speculative bubble. Even oil, which seems to be facing structural issues that would normally be inflationary has had a significant retreat, along with other commodities like copper, lumber and wheat. Some of these declines may only be temporary as markets react to recession threats, but these declines do not happen in a vacuum. They are disinflationary and should be treated as such.

But central banks seem ready to trigger a recession in the name of defeating the beast of inflation even as it seems to be bleeding out on the ground. In June the Federal Reserve raised its benchmark interest rate by 0.75%, and the current view is that the Bank of Canada is likely to do the same in July. All this is sparking deep recession fears that seem to be driving markets lower.

In the background remain genuine issues that seem to be addressed at best haphazardly. Inflation is a real issue making food prices go up, but its been crushing people in housing for years. Even as interest rise and house prices moderate lower, average rents in the GTA were up 18% over the last year. The Canadian government’s response to the mounting costs of living has been to propose a one time payment of $500 to low income renters. That is just a little more than the average increase in rent over the previous 12 months.

In the face of such mounting housing pressure the city of Toronto has done the following things:

- Ban the feeding of birds.

- Consider the leashing of cats.

- Raised development fees 49%.

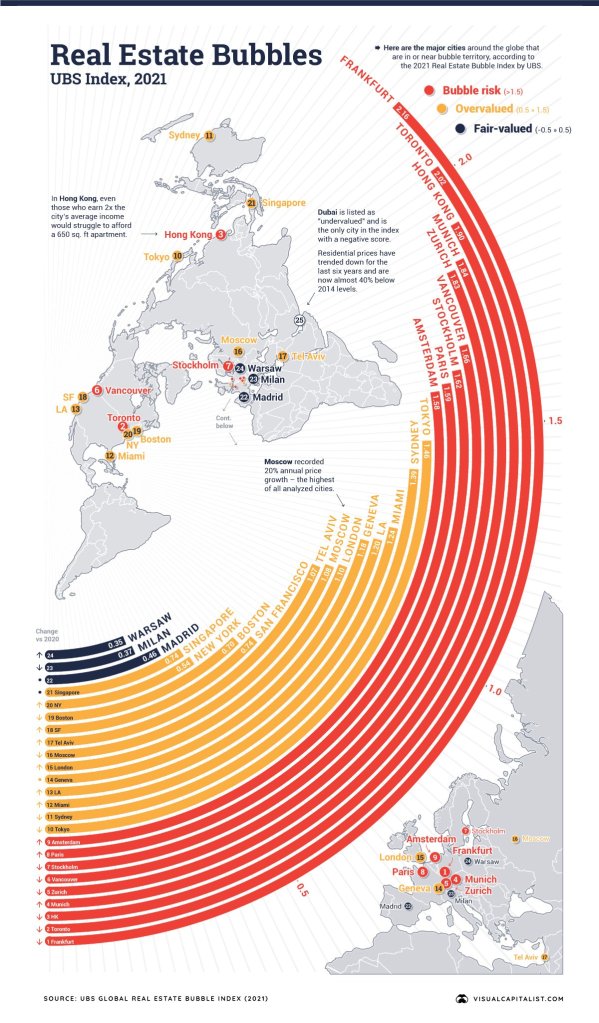

For the record, Toronto is believed to have the second biggest property bubble globally.

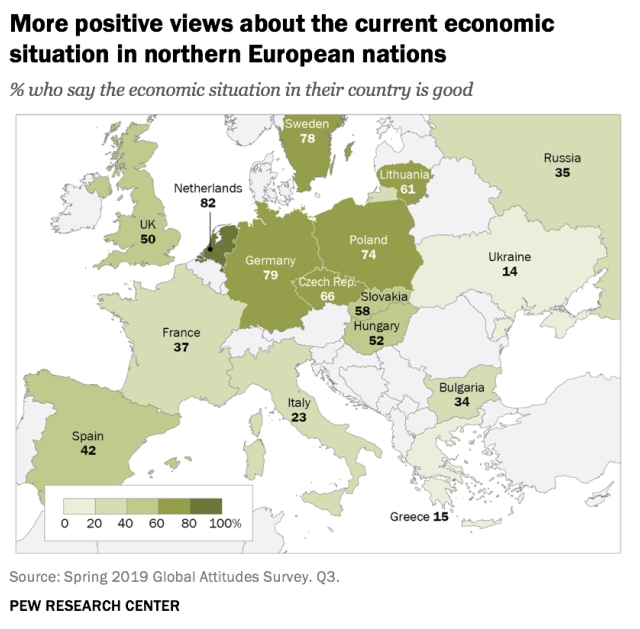

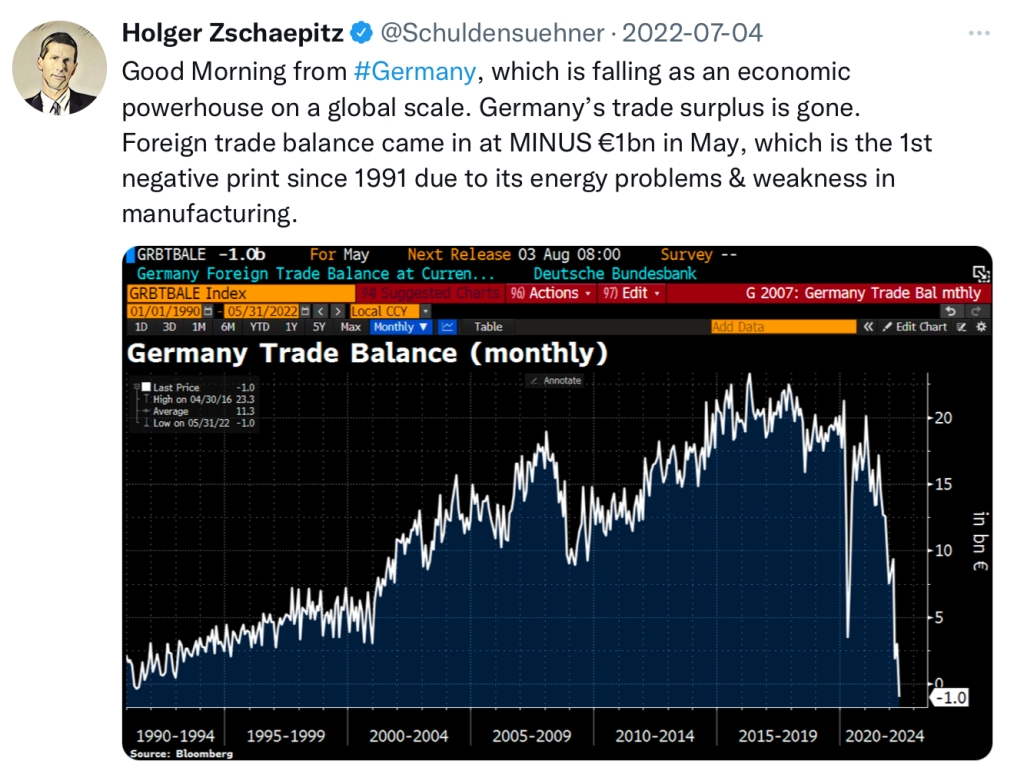

Globally Europe looks to be on the cusp of a serious recession. If North American central banks are looking too aggressive, Europe is struggling to chart a path for its shared currency. Rates have been at record lows but recently the ECB has said it will begin raising rates to tackle inflation. Across the continent the rate of inflation is over 8.1%, but it varies widely country to country, with Germany closer to the average, while Lithuania is at 22%. In the face of mounting inflation the ECB hasn’t raised rates once yet this year, though its expected to this month, even has the European economy and stock markets have been doing worse and worse.

Coincidentally, Germany, who is now both the linchpin in NATO support for Ukraine while simultaneously its weakest link, has seen its economic health crumble due to decisions made years ago to pin Germany’s energy needs to Russian energy supplies. Will Germany today be able to make political decisions that support NATO and the EU even if it means further economic pain for a country that has grown accustomed to being the beneficiary of these arrangements?

It is not just Western or developed nations that are struggling. China is in the middle of some kind of debt bubble in its real estate market, whose impact is harder to know, but will likely be long lasting given its size. Numerous developing nations are on the cusp of debt defaults, the tip of the iceberg being Sri Lanka.

A small island nation off the southern tip of India, Sri Lanka has been reasonably prosperous over the past few decades with an improving standard of living. Yet government mismanagement, graft and a haphazard experiment in organic farming have left the country destitute. Literally destitute. Out of money, gas and food. In the past few days protests have moved beyond general unrest into a full blown revolution, with the Sri Lankan people storming the government and the political leaders fleeing for their lives.

Behind them is El Salvador which has decided to embark on an experiment in making Bitcoin an official currency, a move designed to liberate the country from the tyranny of the World Bank and the US Government. It has instead likely led to a default, financial instability, and a more regressive and authoritarian government.

This year stands out for the complex problems that have grown out of the pandemic, but if we’re serious about the kinds of big problems politicians regularly say that must be tackled, then it raises a question as to whether we are handling them properly, or whether we are making mistakes given what we know right now.

For the last few years I have written or touched on many of these topics; on housing, inflation, crypto currencies and the fragile nature of many of our institutions. And while I am cautious about making grand predictions, it remains worth asking whether we are making smart choices given what we know, and if we are not we should be making greater demands of our elected leaders. And if our elected officials continue to make poor decisions, we as investors should plan accordingly.

Walker Wealth Management is a trade name of Aligned Capital Partners Inc. (ACPI)*

ACPI is regulated by the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (www.iiroc.ca) and a Member of the Canadian Investor Protection Fund (www.cipf.ca). (Advisor Name) is registered to advise in (securities and/or mutual funds) to clients residing in (List Provinces).

This publication is for informational purposes only and shall not be construed to constitute any form of investment advice. The views expressed are those of the author and may not necessarily be those of ACPI. Opinions expressed are as of the date of this publication and are subject to change without notice and information has been compiled from sources believed to be reliable. This publication has been prepared for general circulation and without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. You should not act or rely on the information without seeking the advice of the appropriate professional.

Investment products are provided by ACPI and include, but are not limited to, mutual funds, stocks, and bonds. Non-securities related business includes, without limitation, fee-based financial planning services; estate and tax planning; tax return preparation services; advising in or selling any type of insurance product; any type of mortgage service. Accordingly, ACPI is not providing and does not supervise any of the above noted activities and you should not rely on ACPI for any review of any non-securities services provided by Adrian Walker.

Any investment products and services referred to herein are only available to investors in certain jurisdictions where they may be legally offered and to certain investors who are qualified according to the laws of the applicable jurisdiction. The information contained does not constitute an offer or solicitation to buy or sell any product or service. 16 Past performance is not indicative of future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of principal may occur. Content may not be reproduced or copied by any means without the prior consent of the author and ACPI.

Education represents another significant change that is stultifying the middle class. Education, particularly secondary education took on increasing importance in the 1980s, as those with university degrees started to out earn those with just high school, and those with professional designations (like lawyers and doctors) out paced those with just an undergraduate degree. Would more education fix this? Not really. As the cost of education continues to rise and new technologies filter into even white-collar jobs, young lawyers and accountants struggle to find work, while the management of major companies hangs in longer. The return on education continues to decline even as the costs go up, leaving those who come from wealthier educated families financially better off and better socially connected than those coming from lower income families trying leverage education into higher tax brackets.

Education represents another significant change that is stultifying the middle class. Education, particularly secondary education took on increasing importance in the 1980s, as those with university degrees started to out earn those with just high school, and those with professional designations (like lawyers and doctors) out paced those with just an undergraduate degree. Would more education fix this? Not really. As the cost of education continues to rise and new technologies filter into even white-collar jobs, young lawyers and accountants struggle to find work, while the management of major companies hangs in longer. The return on education continues to decline even as the costs go up, leaving those who come from wealthier educated families financially better off and better socially connected than those coming from lower income families trying leverage education into higher tax brackets.