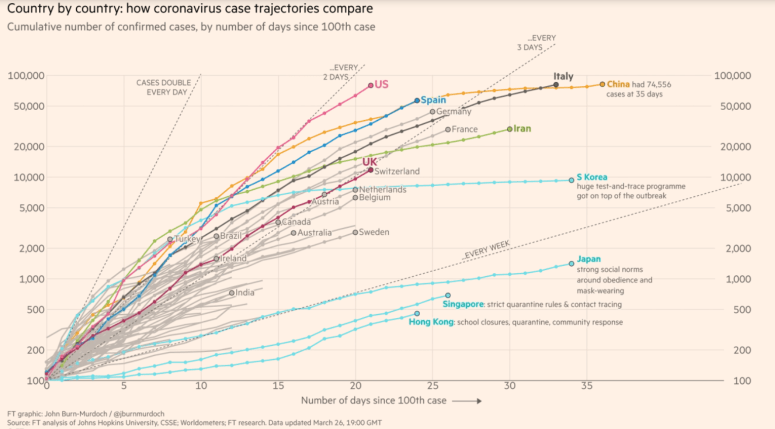

Markets have been bullish the last few days, moving off the most recent lows and easing the strain on investors who have watched their savings tumble by up to 35% since the beginning of the year. Any enthusiasm that this will be a sustained recovery should be tempered by the sheer scope of the economic disruption that we are facing, how early into the problem we currently are, or the potential for a pandemic disaster in the United States, which now has officially more cases than China ever did.

While I remain grateful for the respite we’ve seen, however fleeting, the problem that sticks out in my mind is that of the tangled web of Canadian debt, growing insolvencies, and hundreds of empty condos in downtown Toronto.

Problems rarely exist in isolation, and a problem’s ability to fester, grow and become malignant to the health of the wider body requires an interconnected set of resources to allow its most pernicious aspects to be deferred. In Canada the problem has been long known about, a high level of personal debt that has grown unabated since we missed the worst of 2008. What has allowed this problem to become wide ranging is a banking system more than happy to continue to finance home ownership, a real estate industry convinced that real estate can not fail, and a political class that has been prepared to look the other way on multiple issues including short term rental accommodation, in favour of rising property values to offset stagnant wages.

Recently I was at a round table event on Toronto real estate shortly after the COVID-19 situation started to gain real traction in late February. Benjamin Tal, Deputy Chief Economist for CIBC Capital Markets, described the Canadian real estate scene as “having 9 lives”, every time it seems like house prices can go no higher, something happens to prop up the market. At that moment it was the likely cut in interest rates and an easing of the stress test for mortgages which might breathe more life into the over heated housing market. But that was before international travel dropped off, before national states of emergency, before social distancing, before borders were closed, before essential services, before #lockdowns and #quarantinelife. Tal may not have been wrong conceptually, he simply hadn’t considered that the world might close for business.

Canadian debt has been kept afloat because nothing could conceivably undermine it. And now, in downtown Toronto, condos sit empty. Airbnb hosts have no customers. Costs are mounting and there is no immediate end in sight to the pandemic, no end date that people can bank on. This week 3.3 million Americans filed for EI. In Canada the number was around 1 million. Even the most generous stimulus packages are unlikely to fix a debt problem as big as Canada’s.

True, there is some hope in mortgage deferrals, but scuttlebutt is that banks aren’t very liberal on this matter, telling many that they don’t qualify regardless of political pronouncements. This problem isn’t limited to Toronto. In Dublin rental accommodation jumped by 64% as COVID-19 became a crisis and people began looking for long term tenants to replace the short term ones. Short term thinking by investors, banks, and politicians has facilitated a serious economic problem. But to its enablers it seemed unlikely that there was a scenario that could conceivably expose its flaws.

It is becoming ever clearer that the focus for citizens in the 21st century should be on resilience. Expedience and an assumption that the stability of the recent past is prologue is now a dangerous and toxic combination, creating risks and magnifying bad decisions. Whether the coronavirus ushers in a fiscal reckoning for Canadians, or somehow we sidestep the worst of the crisis through quick action and nimble minds remains to be seen. But how much easier would life be for all had politicians adopted a more hostile stance to Airbnb pushing into the traditional rental markets? Had investors not eagerly dumped savings into condo developments, and had banks been more willing to question the wisdom of lending into what most acknowledged was a real estate bubble.

In December I wrote that the Canadian insolvency rate was the highest it had been in a decade. The city of Toronto recently took action to curb the growth of payday advance loan businesses, as though the problem was the businesses and not people in general need of credit to make ends meet. Whatever is coming in the wake of the COVID-19 shutdown, the issue long predates it. And if insolvencies go up and, for the first time in a long time, a portion of the Canadian real estate sector comes under real pressure there will be a lot of finger pointing at the individuals who have over extended themselves with an illiquid pool of investments. But the truth will be that this problem will have had many facilitators; enablers that were happy to ignore the problem, even help grow it, because they didn’t want to believe that things could go wrong or didn’t see it was their responsibility curb its malignancy.

Information in this commentary is for informational purposes only and not meant to be personalized investment advice. The content has been prepared by Adrian Walker from sources believed to be accurate. The opinions expressed are of the author and do not necessarily represent those of ACPI.

His party was a grab bag of disaffected curmudgeons and, unsettlingly, a number of quasi-racists who were obsessed with immigration.

His party was a grab bag of disaffected curmudgeons and, unsettlingly, a number of quasi-racists who were obsessed with immigration.

In their book “Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support For The Radical Right in Britain” by Matthew Goodwin and Robert Ford, the authors note that the rise of populist UKIP party is “not primarily the result of things the mainstream parties, or their leaders, have said or done…instead, is the result of their inability to articulate, and respond to, deep-seated and long-standing social and political conflicts”.

In their book “Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support For The Radical Right in Britain” by Matthew Goodwin and Robert Ford, the authors note that the rise of populist UKIP party is “not primarily the result of things the mainstream parties, or their leaders, have said or done…instead, is the result of their inability to articulate, and respond to, deep-seated and long-standing social and political conflicts”.

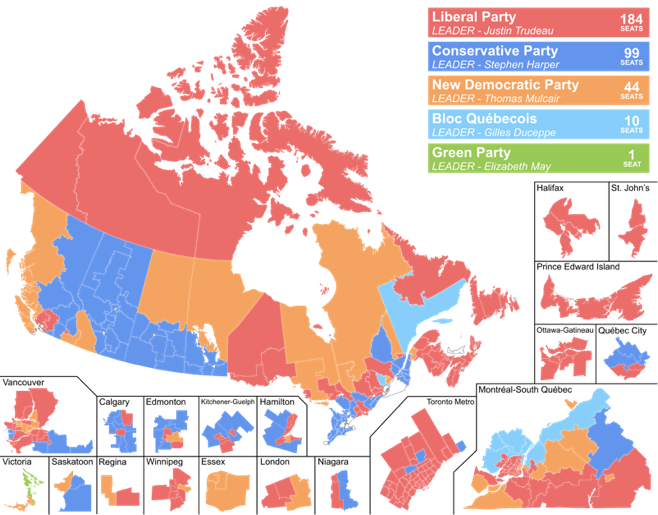

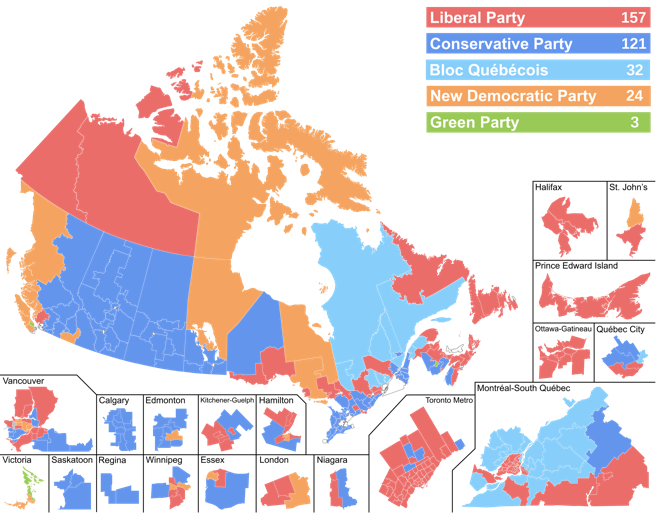

Many populists already exist in our politics. Issues around education, housing and debt remain hot buttons for the electorate. And yet our last election spent far more time focused on a speech by Andrew Scheer from over a decade ago. Does that seem like a political class articulating and responding to long standing and deep seated issues, or one that has learned to master the art of getting elected? Education costs continue to climb and yet the return to students is considerably lower, and prospects much worse for those with only high school diplomas. Debt in Canada has continued to rise, a story that seems evergreen, but insolvencies have also started climbing. Currently insolvencies remain low overall, but given the large amount of Canadian debt, what might it take to push people over the edge? Which politician can honestly say they’ve got a good plan to deal with these problems?

Many populists already exist in our politics. Issues around education, housing and debt remain hot buttons for the electorate. And yet our last election spent far more time focused on a speech by Andrew Scheer from over a decade ago. Does that seem like a political class articulating and responding to long standing and deep seated issues, or one that has learned to master the art of getting elected? Education costs continue to climb and yet the return to students is considerably lower, and prospects much worse for those with only high school diplomas. Debt in Canada has continued to rise, a story that seems evergreen, but insolvencies have also started climbing. Currently insolvencies remain low overall, but given the large amount of Canadian debt, what might it take to push people over the edge? Which politician can honestly say they’ve got a good plan to deal with these problems?

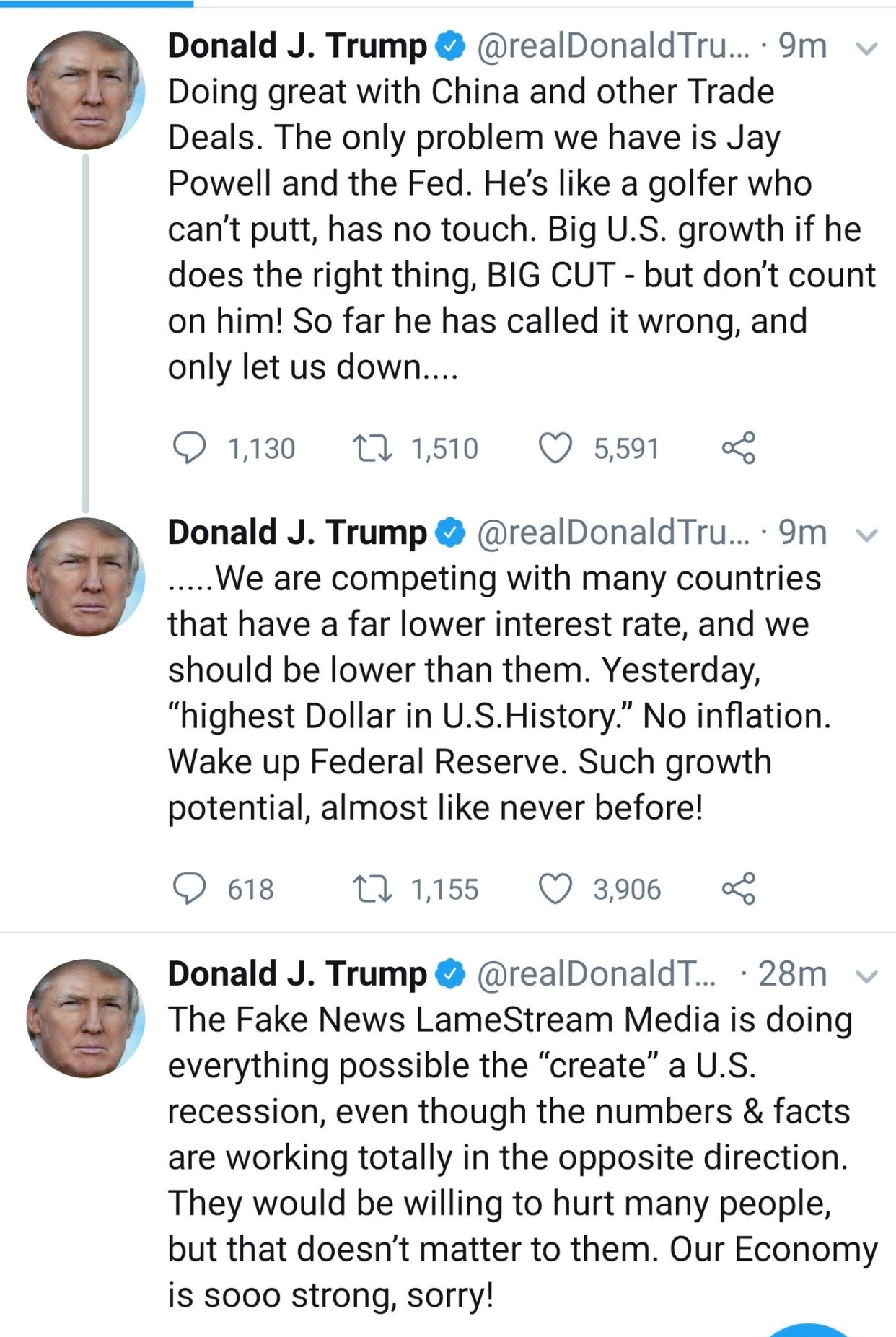

The temptation to assume that everything is about to go wrong is therefore not the most far-fetched possibility. Investors should be cautious because there are indeed warning signs that the economy is softening and after ten years of bull market returns, corrections and recessions are inevitable.

The temptation to assume that everything is about to go wrong is therefore not the most far-fetched possibility. Investors should be cautious because there are indeed warning signs that the economy is softening and after ten years of bull market returns, corrections and recessions are inevitable.