In a year filled with random and unexpected events, hopefully not likely to be repeated anytime soon, the price of oil going negative may stand out as a particularly unusual one. People are familiar with the idea of investments suffering losses and posting negative returns, but for an investment to be negative, to literally be worth less than zero is unique in our history.

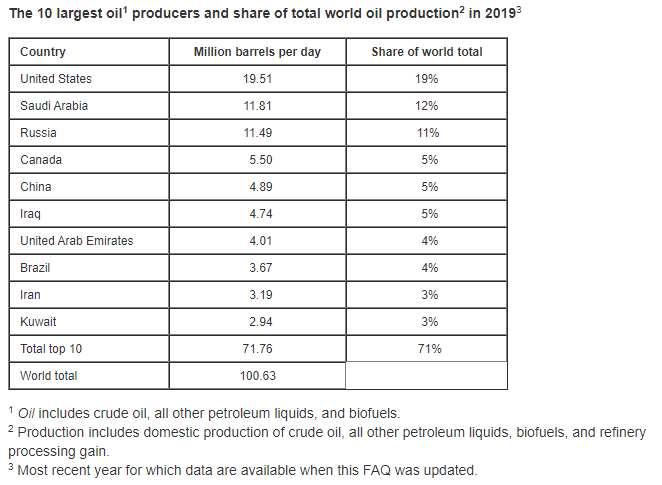

All this, we may say, has been precipitated by an oil war being fought between Russia and Saudi Arabia, made worse by a pandemic that has slashed global demand by 30% and the cumulative effect of a global shift in oil production over the last decade that turned America into the world’s largest producer of oil. We may also assume that the worst hit in this mess are the oil producers themselves.

Certainly in Canada it is easy to assume that it is Canadian producers most at risk from the collapse in oil prices, already suffering trying to get their oil to market more efficiently and cheaply than by train. But while the collapse in oil prices is indeed a headwind for producers, they are not the most at risk at being hurt by the volatility in oil’s spot price.

No, the one most at risk is you, the average investor.

It is important to remember that “financial services” are exactly that, retail products in the financial space. Products that you invest in may reflect a real need by investors, but they also reflect demand. As such it shouldn’t be surprising to discover that products exist that are not needed but are wanted. If someone thinks they can make money providing a vehicle of investment it will likely find its way to the market, for good or ill.

Exchange Traded Funds, the popular low-cost model of investing that has become very common, is where all kinds of investments like this appear. Reportedly there are something like 500 different ETFs in Canada alone. All this variety is good for the consumer, but maybe not for the citizen merely trying to save for their retirement.

Let’s turn our attention back to oil and to fate of investors that, having sensed that the price of oil was so low, they considered investing in the commodity was a “no lose” scenario. In the week before the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) went negative, investors put $1.6 billion into the United States Oil Fund LP (USO ETF). USO was one of a handful of investments that allows investors to try and invest in the actual commodity of oil and skip investing in an oil producing company.

What many of those investors likely didn’t realize is that to get close to the price of oil you have to buy oil contracts that expire very soon. USO did this by holding contracts that mature within the month and then roll those contracts to new contracts for the following month, and so on. This keeps USO’s price and performance close to the spot price (the price the oil is trading for at that moment). But it also means that USO must sell those contracts it holds onto other buyers every month or it risks having to take physical delivery of the oil it holds the contracts for.

The problem should become self-evident. As the May month end contract was approaching, and with oil prices low and storage at a minimum, oil buyers didn’t want USO’s contracts, and USO couldn’t physically receive the shipment of the oil. It had to get rid of the contracts at any price, and that’s just what they did, paying buyers to take the oil contracts off their hands.

ETFs, Mutual Funds and a host of other investments make it seem as though investing has few barriers, with ease of access making experts of us all. But that isn’t the case. The unique qualities of a product, the mechanics of how some investments work and ignorance about the history of a market sector can spell danger for novice investors that assume markets are simple. In Canada there are only a few investments that deal directly in the commodity of oil; the Auspice Canadian Crude Oil ETF (due to be closed May 22 of this year), the Horizon BetaPro Crude Oil Daily Bear and Daily Bull ETFs (HOD and HOU respectively, both of which may have to liquidate. Horizon ETFs have advised investors NOT TO BUY THEIR OWN ETFS!) and lastly the Horizon’s Crude Oil ETF, which uses a single winter contract to reduce risk but will radically alter the performance compared to the spot price.

Many investments are not what they seem, maintaining a superficial exterior of simplicity that masks the realities of a sector or structure that can be a great deal riskier than an investor expects. In 2018 investors that had purchased ETFs that traded the inverse of the VIX (a “fear gage” that tracks investors sentiment about the market) suffered huge losses when the Dow Jones had its (then) largest one day drop ever, wiping out 80% of the value of some of these investments. Then, like now, investors had a poor understanding of what they owned and were easily blindsided by events they considered unlikely.

As I’m writing this I see reports out that suggest the price of oil could once again go negative. Whether they do or not is irrelevant. It is enough to know that they can and that investors will have little defence against a poorly constructed product that has the ability to go to zero. Before last week the USO ETF owned 25% of the outstanding volume of May’s WTI contracts. That was a concentration of risk that its investors just didn’t realize or understand. Today its clear just how dangerous that investment was. Investors owe it to themselves to get some real advice on what they invest in, and make sure those investments fit into their risk profile and investment goals.

Information in this commentary is for informational purposes only and not meant to be personalized investment advice. The content has been prepared by Adrian Walker from sources believed to be accurate. The opinions expressed are of the author and do not necessarily represent those of ACPI.