This was written on Friday, November 6th. Since then the election has been called for Joe Biden.

It’s Friday, November 6th, and Pennsylvania seems to be looking like it will go to Biden. With four battleground states showing narrow Biden leads, the math seems inescapable. Biden will be the 46th president of the United States.

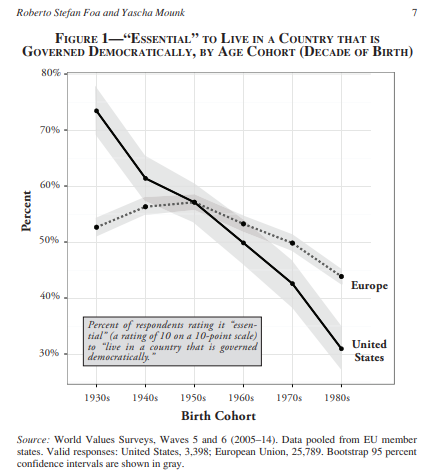

The narrowness of this victory is unsettling. A record turnout for both Republicans and Democrats, the largest turnout since the 1960s of the electorate, the largest percentage of votes by visible minorities for a Republican candidate since Richard Nixon, only showed that American remains a polarized land. The hoped for “Blue Wave” as Americans repudiated Trump and his enablers did not materialize. The Senate will likely remain in the hands of Republicans. The House of Representatives may flip to Republicans too.

Even now, after all that has unfolded over the last four years, much of what brought Trump to power; anger at a failure of the establishment to protect jobs, uncertainty about the ethnic and cultural future of the United States, the erosion of the middle class, the simultaneous exhaustion of being THE global superpower while being blamed for being one. These issues linger, promised but unaddressed by Trump, ignored by his party and fueling alienation in the general populace.

Other, more persistent aspects of American culture have also been on display. Since Richard Hofstader first wrote his book Anti-Intellectualism in American Life in 1962 (He calls Eisenhower “conventional in mind, (and) relatively inarticulate” – cruel words for one of America’s best remembered Republican presidents) Americans continue to lament, often publicly, just how stupid they find one another. Whether it is over face masks, the environment, or conspiracies about “the deep state”, Americans remain shockingly divided, often down the middle.

But with Biden elected (presuming he survives all the legal attacks and mandated recounts) and once the final vote tallies are certified in a few weeks, a corner will have been turned. Trump, in his role as a lame duck president will likely shore up personal protections, lash out at allies that failed to defend him, denounce democratic institutions that have allowed for his failure, and presumably pardoning those in his close circle and looking to shield himself from any future prosecution. Biden will hopefully find some common ground in the Senate and House of Representatives that will allow business to proceed, but it seems safe to assume that the most ambitious parts of the Democrat’s wish list won’t make it into law. Similarly, hopes for a Trump sized stimulus package will now also be dashed by a Republican establishment always uncomfortable with Trump’s lavish spending but fearful of his wrath.

From the perspective of the investment world this seems to be a continuation of the status quo. Biden does not possess Trump’s unique skill at bullying, backed by the threat of his irate voters. Instead the hope will be that he can better negotiate with Republicans. But with the election leaving the GOP in a strong legislative position there will be little appetite for aggressive policy shifts. Instead we should expect tepid fiscal stimulus, continued strength in businesses profiting from the pandemic (like tech stocks) and a wider, more subdued recovery as we face the immediate economic uncertainty.

So often we think big things represent monumental shifts. The election of Trump was one such event, but in the end his legacy will be a great deal smaller, and I suspect better thought of, than we might guess now. His ignorance, narcissism, and sociopathy were critical flaws in a man that showed great skill in reading the American public. His few achievements, including peace between Israel and several Arab states, challenging China and striking some kind of trade deal, and boosting American military spending were not missteps. His useless forays into border walls and needless antagonism of American allies will not be missed. At the outset of his presidency he even had the foresight to surround himself with some accomplished and knowledgeable people. In the end Donald Trump’s biggest enemy was himself. Were Trump a more competent and less incurious man he could have been a formidable political force. Instead, his certainty in his own skill and inability to adapt made him an aspiring autocrat in search of a balcony.

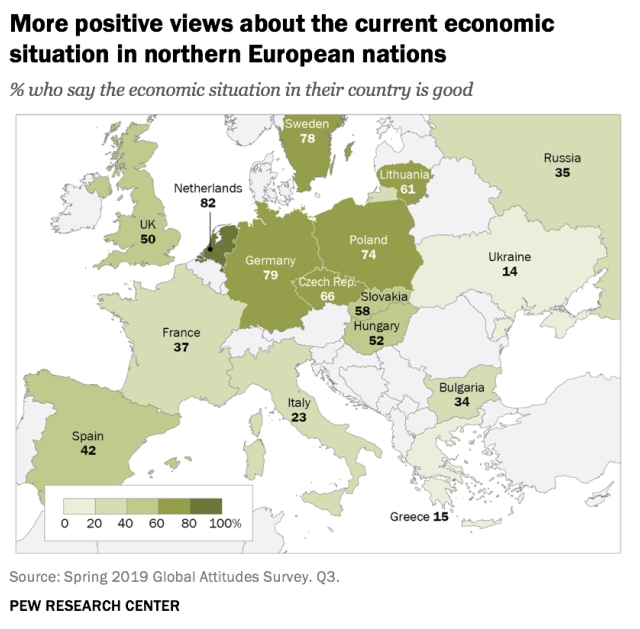

To cultural observers, the election of Trump should be a reminder that small things that go unnoticed or ignored often prove to be bigger issues. The sudden mysterious outbreak of an unknown form of pneumonia in Wuhan at the end of 2019. The subtle shift in economic thinking by political leaders across the West. A demographic trend that sees a generation shrinking, maybe even incapable of marrying. The rapid economic growth of an often-overlooked part of the world. It may even be the surprising growth of visible minority voters for a candidate long believed to be their enemy. These quiet things, hiding in the corners, may be the issues that guide our future rather than the bombast of men like Donald Trump.

In 2015 I wrote that “You don’t have to love people like Rob Ford or Donald Trump, but their ability to change the political terrain, to question traditional assumptions about the electorate and undo the laziness of identity politics is healthy for a democracy, even when you don’t like the messenger.” Looking back on four years, I am only desiring a return to normalcy, but with so many of the issues that brought Trump to the White House still unaddressed I’m afraid that whatever normalcy Joe Biden can bring will be short lived.

Information in this commentary is for informational purposes only and not meant to be personalized investment advice. The content has been prepared by Adrian Walker from sources believed to be accurate. The opinions expressed are of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Aligned Capital Partners Inc.

Education represents another significant change that is stultifying the middle class. Education, particularly secondary education took on increasing importance in the 1980s, as those with university degrees started to out earn those with just high school, and those with professional designations (like lawyers and doctors) out paced those with just an undergraduate degree. Would more education fix this? Not really. As the cost of education continues to rise and new technologies filter into even white-collar jobs, young lawyers and accountants struggle to find work, while the management of major companies hangs in longer. The return on education continues to decline even as the costs go up, leaving those who come from wealthier educated families financially better off and better socially connected than those coming from lower income families trying leverage education into higher tax brackets.

Education represents another significant change that is stultifying the middle class. Education, particularly secondary education took on increasing importance in the 1980s, as those with university degrees started to out earn those with just high school, and those with professional designations (like lawyers and doctors) out paced those with just an undergraduate degree. Would more education fix this? Not really. As the cost of education continues to rise and new technologies filter into even white-collar jobs, young lawyers and accountants struggle to find work, while the management of major companies hangs in longer. The return on education continues to decline even as the costs go up, leaving those who come from wealthier educated families financially better off and better socially connected than those coming from lower income families trying leverage education into higher tax brackets.

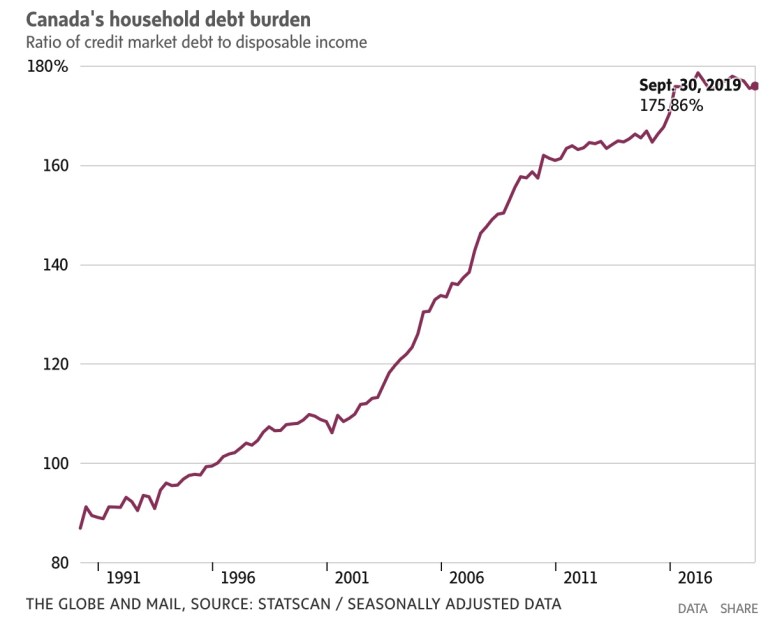

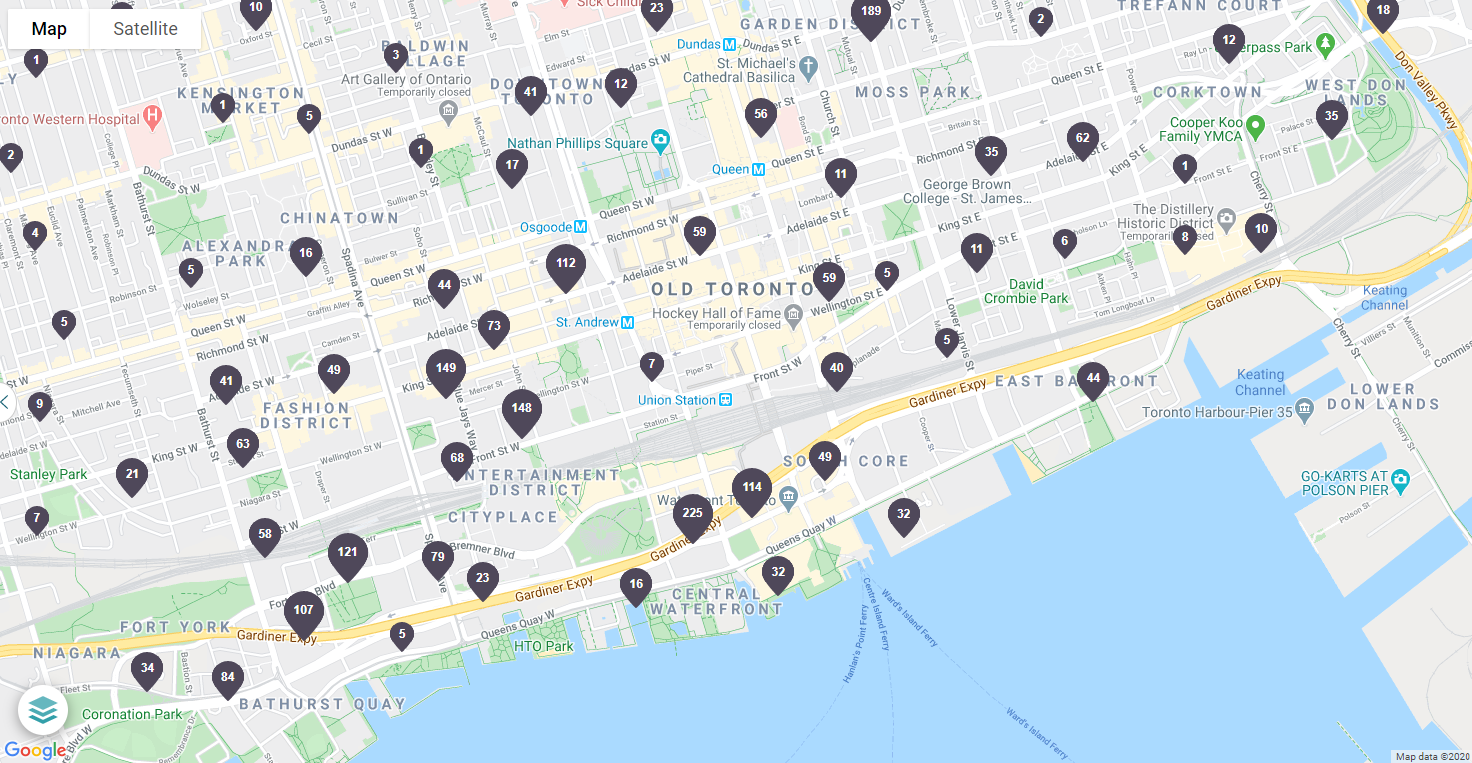

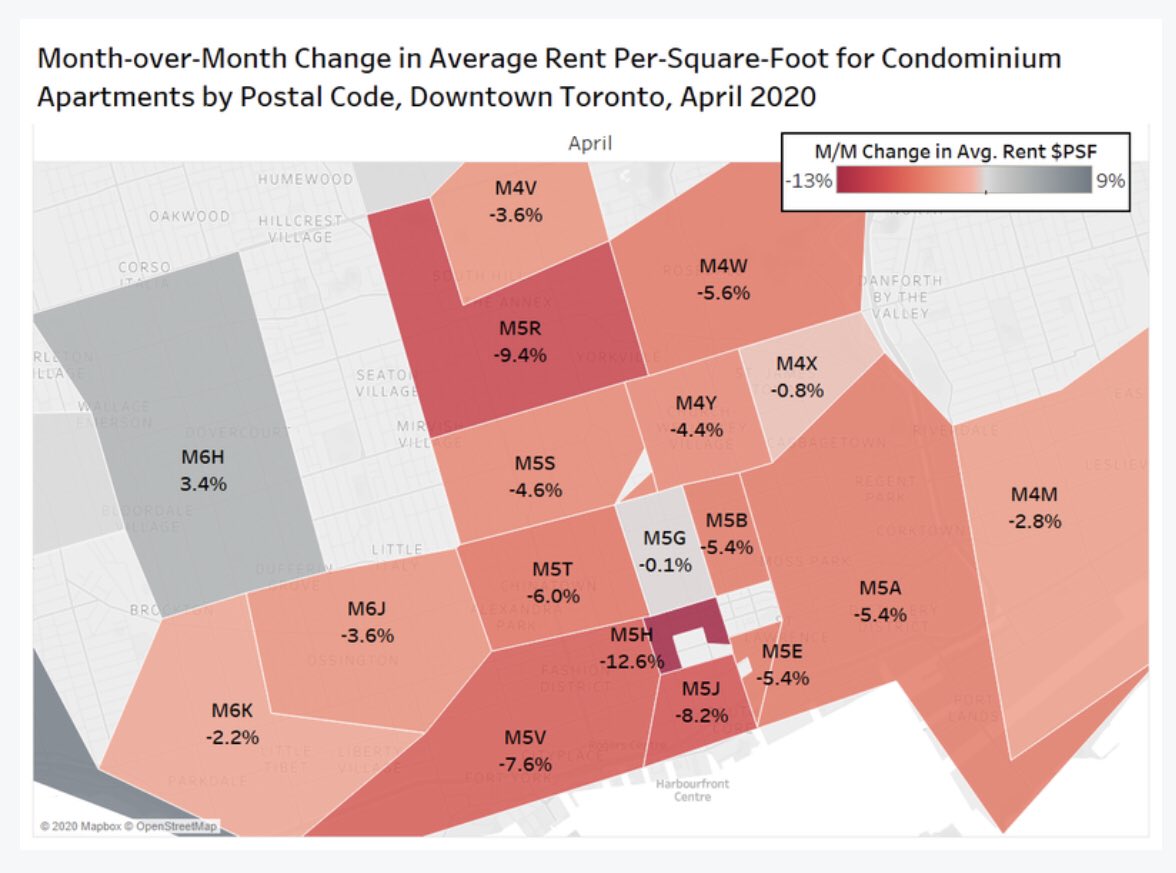

Real estate remains at the heart of the Canadian economic story for the last 20 years. Appreciating housing prices are the chief source for growth in Canadian families’ net worth. Borrowing to buy houses and borrowing against home equity remain our chief sources of debt. Our politics revolves around the tension of needing more housing in certain highly desirable areas while preserving those areas from over development. That dynamic has revolved around a status quo that seemed to have no conceivable end. The pandemic may have radically altered the Canadian real estate landscape regardless of how people feel about it or what they want. Whether we can walk back changes of this magnitude remains very much unknowable. For now we can only watch the changes our society and economy are undergoing and hope that what we are witnessing will be for the best, those changes that have happened, and those yet to come.

Real estate remains at the heart of the Canadian economic story for the last 20 years. Appreciating housing prices are the chief source for growth in Canadian families’ net worth. Borrowing to buy houses and borrowing against home equity remain our chief sources of debt. Our politics revolves around the tension of needing more housing in certain highly desirable areas while preserving those areas from over development. That dynamic has revolved around a status quo that seemed to have no conceivable end. The pandemic may have radically altered the Canadian real estate landscape regardless of how people feel about it or what they want. Whether we can walk back changes of this magnitude remains very much unknowable. For now we can only watch the changes our society and economy are undergoing and hope that what we are witnessing will be for the best, those changes that have happened, and those yet to come.

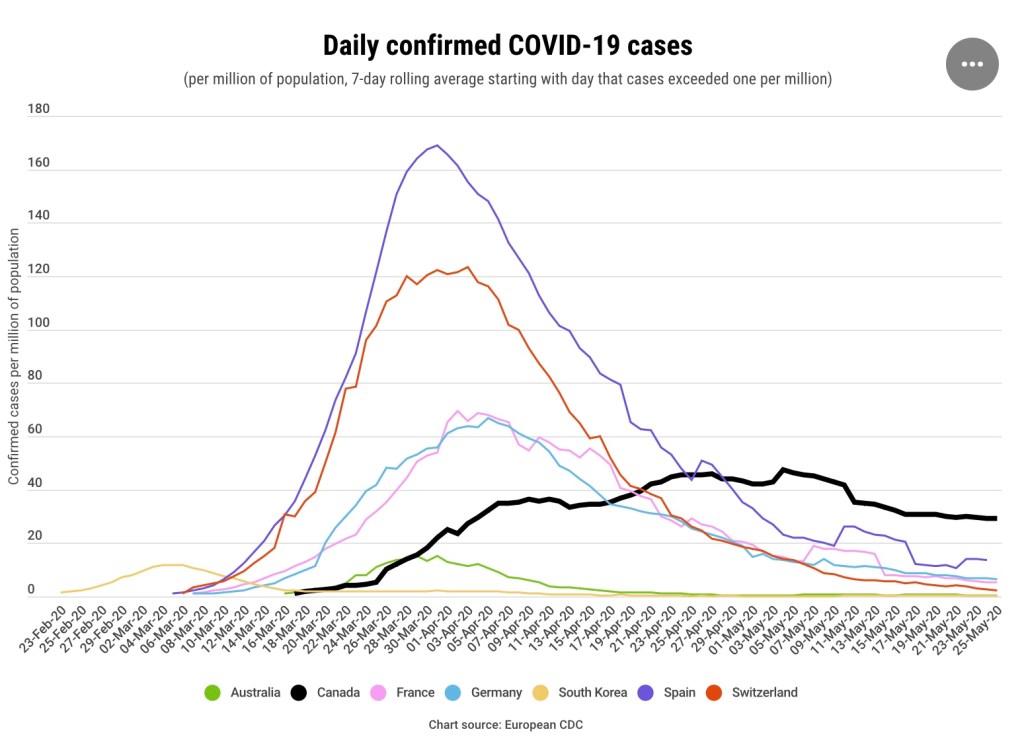

But what of the predictions we keep hearing about? That life will be forever changed by the events we’re living through? While I have a great deal more to say about the nature of prognostication, I’ll keep my comments here brief. In general history shows that humans don’t tend towards radical changes following big, but temporary upheavals. Instead, crises like the one we are living through emphasize existing weaknesses within the society.

But what of the predictions we keep hearing about? That life will be forever changed by the events we’re living through? While I have a great deal more to say about the nature of prognostication, I’ll keep my comments here brief. In general history shows that humans don’t tend towards radical changes following big, but temporary upheavals. Instead, crises like the one we are living through emphasize existing weaknesses within the society.