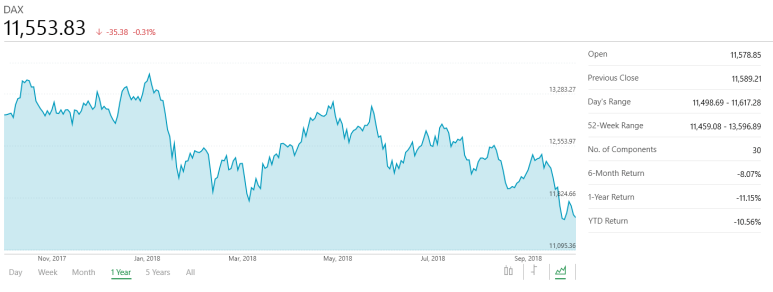

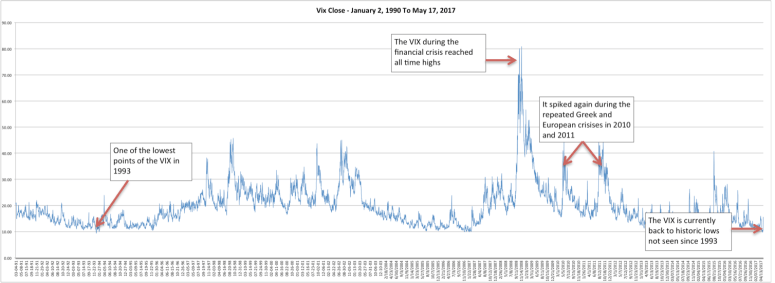

This past week markets had a sudden and sustained sell off that lasted for two days, and though they bounced back a little on Friday, US markets had several negative sessions. The selloff in US markets, which began on Wednesday and extended into Thursday, roiled global markets as well, with extensive selling through Asia and Europe on Wednesday evening/Thursday morning. At the end of the week Asian, European and Emerging markets looked worse than they already were for the year, and US markets had been badly rattled. This week has seen an extension of that volatility.

Explanations for sudden downturns bloom like flowers in the sun. Investors and business journalists are quick to latch onto an explanation that grounds the unexpected and shocking in rational sensibility. In this instance blame was handed to the Federal Reserve, where members had been quoted recently talking about higher than expected inflation forcing up lending rates at an accelerated pace. This account was so widely accepted that Donald Trump was quoted as saying that “The Fed has gone crazy”, a less than surprising outburst.

I tend to discount such explanations about market volatility. For one, it seeks to neuter the truth of markets as large complex institutions that are subject to multiple forces of which many are simply invisible. Second, by pretending that the risk in markets is far more understandable than it really is, investors are encouraged to take up riskier positions and strategies than they rightly should and ignore advice that has proven effective in managing risk. Finally, I have a personal dislike for the façade of “all-knowingness” that comes along after the fact by people who have parlayed luck into “expertise”. Markets are risky and complex, and it would be better if we treated them like a vicious animal that’s only partially domesticated.

In fact, as markets continue to grow with technology and various new products, complexity continues to expand. At any given time markets are subject to small investors, professional brokers, pension funds, algorithm driven trading programs, mutual fund managers, exchange traded funds and even governments, all of whom are trying to derive profits.

So what does that tell us about markets, and what should we take from the recent spike in volatility? One way to think about markets is that they operate on two levels, a tangible level based on real data and expectations set by analysts, and another that trades on sentiment. On the first level we tend to find people who advocate for “bottom up investing”, or the idea that corporate fundamentals should be the sole governor of stock’s price. If you’ve ever heard someone discuss a stock that’s “under-performing,” “undervalued,” “out of favor,” or that they are investing on the “principles of value” this is what they are referring to. People who invest like this believe that the market will eventually come around to realizing that a company hasn’t been priced correctly and tend to set valuations that tell them when to buy and sell.

The second level of investing is based on sentiment, informed by the daily influx of headlines, rumour and conspiracy that clogs our news, email inboxes and youtube videos. This is where most investors tend to hang their hat because its where the world they know meets their investments. Most people aren’t analyzing a specific bank, but they may be worried a housing bubble in Canada, or the state of car loans, or the benefits of a recent tax cut or trade war. The sentiment might be best thought of as the fight between good and bad news informing optimism and pessimism. If a bottom up investor cares about a company they may ignore general worry that might overwhelm a sector. So if there is a change in in the price of oil, a value investor may continue to own a stock while the universe of sentiment sees a widespread selling of oil futures, oil companies, refining firms and downstream products.

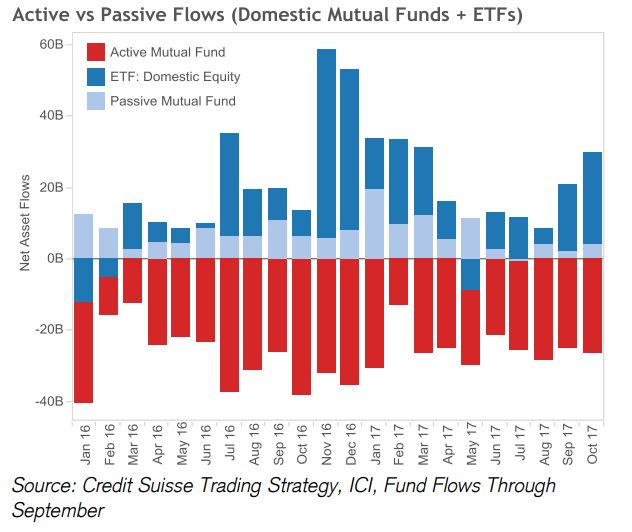

As you are reading this you may believe you’ve heard it before. Indeed you have, as our advice has remained consistent over the years. Diversification protects investors and retirement nest eggs better than advice that seeks to “beat the market” or chases returns. However, it seems to me that the market sentiment is undoubtedly a stronger force now than its ever been before. As more investors come to participate in the market and passive investments have grown faster than other more value focused products, sentiment easily trumps valuations. Since we’re always sitting atop a mountain of conflicting information, some good and some bad, whichever news happens to dominate quickly sets the sentiment of the markets.

You don’t have to take my word for it either. There is some very interesting data to back this up. Value investing, arguably the earliest form of standardized profit seeking from the market, has remained out of favor for more than a decade. Meanwhile the growth of ETFs has continued to pump money into the fastest growing parts of the market, boosting their returns and attracting more ETF dollars. When the market suddenly changed direction on Wednesday, the largest ETF very quickly went from taking in new dollars to a mass exodus of money, pushing down its value and the value of the underlying assets. At the same time some of the worst performing companies went to being some of the best performing in a day.

So what’s been going on? The markets have turned negative and become much more volatile because there is a lot of negative news at play, not because interest rates are set to go up too quickly. Sentiment, that had been positive on tech stocks like Amazon and Google gave way to concern about valuations, and with it opened the flood gates to all the other negative news that was being suppressed. Brexit, the Italian election, the rise of populism, currency problems in Turkey, a trade war with China and rising costs everywhere came to define that sentiment. As investors begin to feel that no where was safe, markets reflected that view.

Our advice remains steadfast. Smart investing is less about picking the best winner than it is about having the smartest diversification. A range of solutions across different sectors and styles will weather a storm better, and investors should be wary of simplistic answers to market volatility. Markets always have the potential to be volatile, and investors should always be prepared.

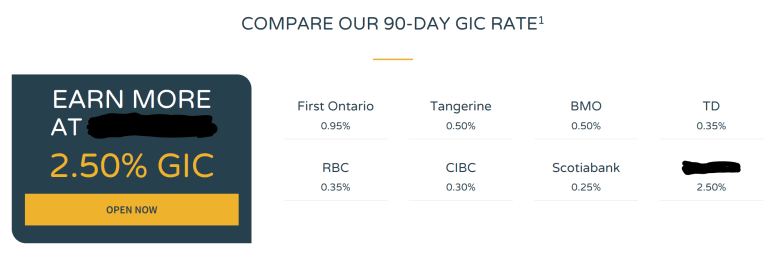

To say that Canadians aren’t financially literate may seem a touch unfair, but everywhere you look we find testaments to this unavoidable fact. Credit cards, car loans, mortgage rates and even how returns are calculated are a confusing mess for most people. The math that governs these relationships is often opaque and can feel misleading, and its complexity assures that even if some do understand it, the details will only be retained by a tiny minority.

To say that Canadians aren’t financially literate may seem a touch unfair, but everywhere you look we find testaments to this unavoidable fact. Credit cards, car loans, mortgage rates and even how returns are calculated are a confusing mess for most people. The math that governs these relationships is often opaque and can feel misleading, and its complexity assures that even if some do understand it, the details will only be retained by a tiny minority.

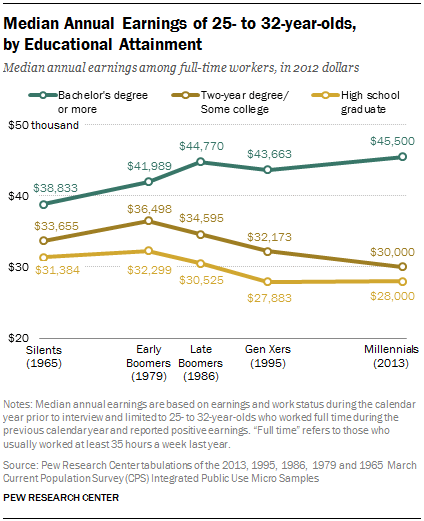

Armed with that info you might feel like the whole project makes sense. In reality, there are lots of questions about inflation that should concern every Canadian. Consider the associated chart from the American Enterprise Institute. Between 1996 – 2016 prices on things like TVs, Cellphones and household furniture all dropped in price. By comparison education, childcare, food, and housing all rose in price. In the case of education, the price was dramatic.

Armed with that info you might feel like the whole project makes sense. In reality, there are lots of questions about inflation that should concern every Canadian. Consider the associated chart from the American Enterprise Institute. Between 1996 – 2016 prices on things like TVs, Cellphones and household furniture all dropped in price. By comparison education, childcare, food, and housing all rose in price. In the case of education, the price was dramatic.

In Ontario the price of food is more expensive, gas is more expensive and houses (and now rents) are also fantastically more expensive. To say that inflation has been low is to miss a larger point about the direction of prices that matter in our daily lives. The essentials have gotten a lot more expensive. TVs, refrigerators and vacuum cleaners are all cheaper. This represents a misalignment between how the economy functions and how we live.

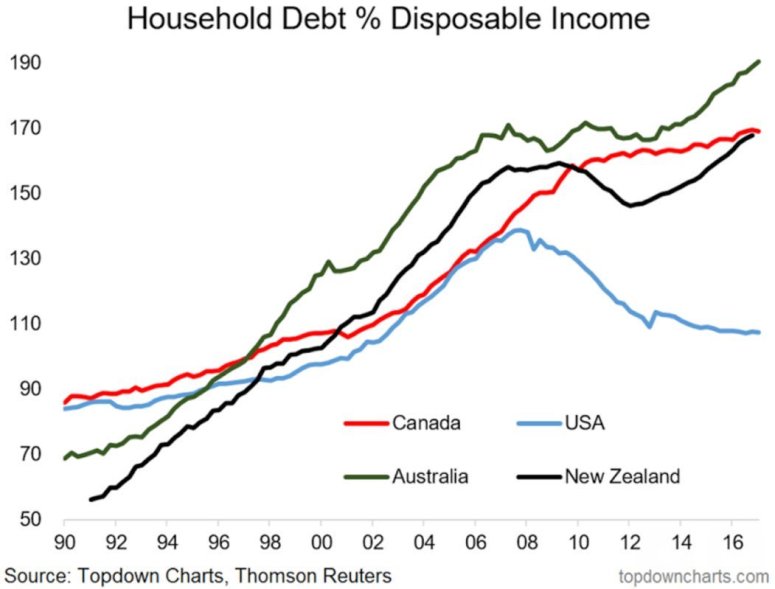

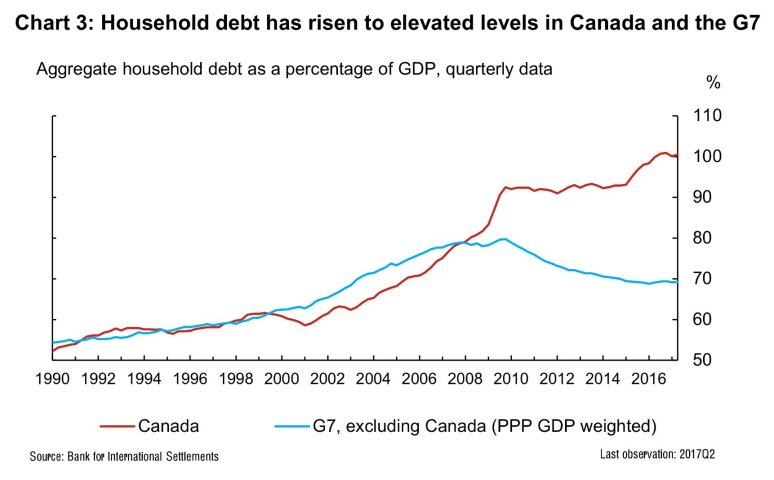

In Ontario the price of food is more expensive, gas is more expensive and houses (and now rents) are also fantastically more expensive. To say that inflation has been low is to miss a larger point about the direction of prices that matter in our daily lives. The essentials have gotten a lot more expensive. TVs, refrigerators and vacuum cleaners are all cheaper. This represents a misalignment between how the economy functions and how we live.  Economic data should be meaningful if it is to be counted as useful. A survey done by BMO Global Asset Management found that more and more Canadians were dipping into their RRSPs. The number one reason was for home buying at 27%, but 64% of respondents had used their RRSPs to pay for emergencies, for living expenses or to pay off debt. These numbers dovetail nicely with the growth in household debt, primarily revolving around mortgages and HELOCs, that make Canadians some of the most indebted people on the planet.

Economic data should be meaningful if it is to be counted as useful. A survey done by BMO Global Asset Management found that more and more Canadians were dipping into their RRSPs. The number one reason was for home buying at 27%, but 64% of respondents had used their RRSPs to pay for emergencies, for living expenses or to pay off debt. These numbers dovetail nicely with the growth in household debt, primarily revolving around mortgages and HELOCs, that make Canadians some of the most indebted people on the planet.

In his excellent book

In his excellent book

If there was ever going to be a moment to gain some clarity about what the Brexit would truly and ultimately mean, Friday was the day. Following the win by the leave camp, markets were sent reeling on the uncertainty stirred up by the referendum, and by the day’s end Britain had gone from being the

If there was ever going to be a moment to gain some clarity about what the Brexit would truly and ultimately mean, Friday was the day. Following the win by the leave camp, markets were sent reeling on the uncertainty stirred up by the referendum, and by the day’s end Britain had gone from being the