Falling inflation, terrible economic news and a general sense of dread for the future seems to have once again become the primary descriptive terms for Europe. Earlier this year things seemed to have improved dramatically for the continent. On the back of the German economic engine much of the concern about the EU had been receding. 2013 had been a good year for investors and confidence was returning to the markets. Lending rates were dropping for the “periphery nations” like Portugal, Greece and Ireland, giving them a fighting chance at borrowing at affordable rates. But first came the Ukrainian/Russia problem which caused a great deal of geo-political instability in the markets. Then came October.

Falling inflation, terrible economic news and a general sense of dread for the future seems to have once again become the primary descriptive terms for Europe. Earlier this year things seemed to have improved dramatically for the continent. On the back of the German economic engine much of the concern about the EU had been receding. 2013 had been a good year for investors and confidence was returning to the markets. Lending rates were dropping for the “periphery nations” like Portugal, Greece and Ireland, giving them a fighting chance at borrowing at affordable rates. But first came the Ukrainian/Russia problem which caused a great deal of geo-political instability in the markets. Then came October.

I don’t know if Mario Draghi cries himself to sleep some nights, but I wouldn’t blame him. Despite the best efforts of the ECB, Europe looks closer to being in a liquidity trap then ever. Borrowing rates are not just low, they’re negative, with the ECB charging banks to now to deposit money with them. October also ushered in a string of bad news. For Germany, easily the biggest part of the Eurozone’s hopes for an economic recovery, sanctions against Russia have hurt the manufacturing sector. Germany began the month announcing a steep and unexpected decline in manufacturing of 5.7% in August, the biggest since 2009. This news was followed by criticisms of Germany’s government for not doing more infrastructure investment and being too obsessed with their strict budget discipline. Yesterday 25 banks in the Eurozone failed a stress test, a test that was meant to allay fears about the health of the financial sector.

For Europe then things look bad and even if the situation corrects itself over the next few months (sudden shifts in the economy may not always be permanent and can bounce back quickly) the concerns over Europe’s future will likely undermine any efforts by the ECB to properly stimulate the broad economy and encourage investment on a mass scale. By comparison it looks like the United States is having a party.

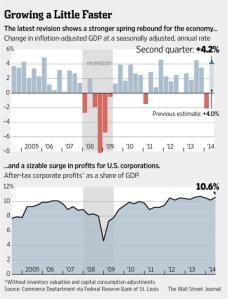

The US economy seems to be on track to grow, and as the world’s biggest economy (though there is some dispute) the country is fighting fit and especially lean. Cheap oil from shale drilling is helping the manufacturing sector, making the United States more competitive than South Korea, the UK, Germany and Canada, and the sudden drop in the price of oil is a boon to the US consumer to the tune of nearly 50 billion dollars. Consumer confidence is up, as is spending. Debt levels are down, both for companies and households. Most importantly the economy seems to be tipping over into an expansionary phase, with corporations finally starting to put some of their money to work.

The coming months could be interesting for investors as we return to a time where once again focus is on the US as the world’s primary economy. The concerns of 2008, that the American consumer was done, the country had seen its best days and its corporations would never recover seem far fetched now. Worries over hyper-inflation are as distant as a the never arriving (but inevitable) rate hike from the Federal reserve. Worries about Great Depression levels of unemployment are problems of other nations, not the US with its now enviable 5.9%, now encroaching on full employment. Old villains seem vanquished and even Emerging Markets, long thought to be entering their own golden era, are now taking a back seat to the growing opportunities coming out of the US.

The concerns of 2008, that the American consumer was done, the country had seen its best days and its corporations would never recover seem far fetched now. Worries over hyper-inflation are as distant as a the never arriving (but inevitable) rate hike from the Federal reserve. Worries about Great Depression levels of unemployment are problems of other nations, not the US with its now enviable 5.9%, now encroaching on full employment. Old villains seem vanquished and even Emerging Markets, long thought to be entering their own golden era, are now taking a back seat to the growing opportunities coming out of the US.

Investors should sit up and take note. It’s possible that the best is still yet to come for the US markets, and if market conditions continue to improve this bull market could prove to be a long one.