I ‘ve just had a chance to watch the movie The Big Short, based on the book of the same name by Michael Lewis. Michael Lewis has made a name for himself as a writer for being able to explain complex issues, often involving sophisticated math that befuddles the general population but is responsible for much of the financial chaos that has defined the last decade.

‘ve just had a chance to watch the movie The Big Short, based on the book of the same name by Michael Lewis. Michael Lewis has made a name for himself as a writer for being able to explain complex issues, often involving sophisticated math that befuddles the general population but is responsible for much of the financial chaos that has defined the last decade.

The principle of our story is Dr. Michael Burry, a shrewd investor whose unique personal qualities gives him the patience to tear apart one of the most complicated financial structures in modern finance. Having done that he creates a new market for a few people who had the foresight to see the US housing bubble and how far the crash might reach. The story is captivating and the tension builds to what we know is the inevitable conclusion of the worlds biggest crash, but there is a problem with the story.

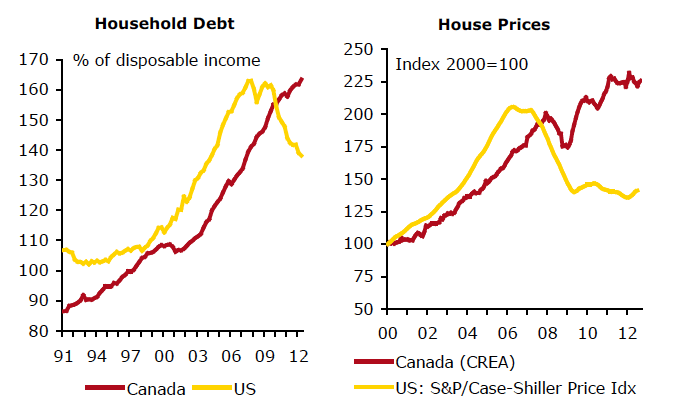

No matter what they do in the movie, we know how it all ends. That hindsight undercuts the real tension in the film, the risk that these few traders and hedge fund managers took with other people’s money to bet against what were largely considered to be safe investments. In some ways, the US housing crash is unique because of how much institutionalized corruption had seeped into the system. The ratings agencies who sold their AAA ratings for the business, the mortgage brokers who pushed through unfit candidates into subprime adjustable rate mortgages, the analysts and financial specialists that repackaged low grade mortgages into AAA rated bonds; it took all of them and more to create the biggest market bubble since the South Sea.

Their smart move seems like lock, but if you look past the drama the heroic brokers of our story were taking a huge gamble with other people’s money. From Dr. Michael Burry down through the rest of the characters, hundreds of millions, billions even, were tied up in investments that few understood but carried incredible potential for losses. The confidence that our heroes show in demanding “half a billion more” as they come to understand the scope of the problem seem smart in hindsight, but they were making big bets. Bets that could have easily ruined people’s lives and finances.

This is the true nature of risk. Things are only certain in hindsight. At the moment we need to make decisions rarely do we possess the kind of clarity that we believe we should have when dealing with markets. If we look to current markets what can we honestly say we know about tomorrow? Markets are chaotic, oil prices are in the tank, central bankers are talking about negative interest rates (while some have gone and done it), and then we will have 2 or 3 days of market rallies. What picture should we draw from this? What certainty do we have about tomorrow’s performance?

Our problem is that when we are inclined towards certainty we are also inclined towards fantastic risk. In fact we won’t even believe there is risk if we are certain of an outcome. And we are prone to lionizing people who risk it all and are proved to be right, while forgetting all those people who made similar gambles and lost everything, leading us to repeat a mistake that has undone many.

The story we need isn’t the one about the people who bet big and won. We need the story about the people who bet smart and navigated confusing and risky markets and came out fine. That story sadly won’t have the kind of impact or drama that we long for in a movie, but it’s the story that each and every investor should want to be part of.

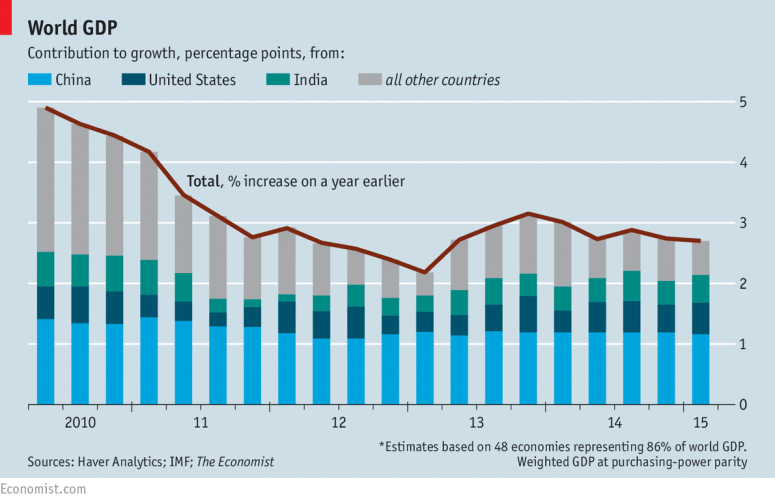

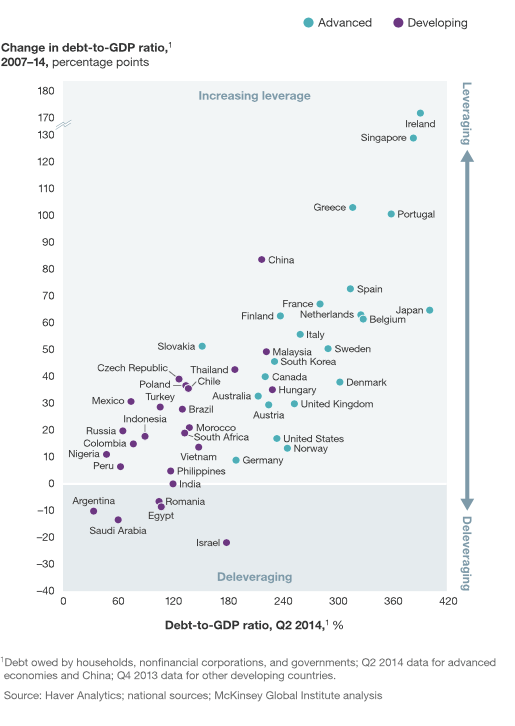

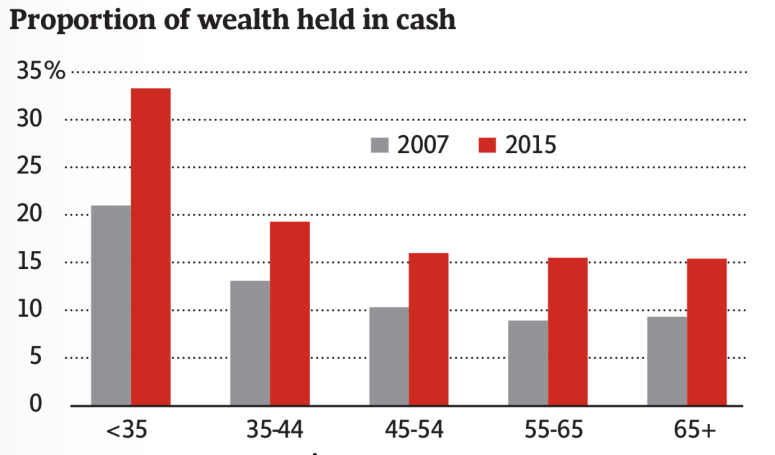

Since 2008 governments the world over have tried to fight the biggest banking collapse since the great depression with modest success. Eight years on and you would be loath to say that the world has turned a corner, ushering in a return of unrestrained economic growth.

Since 2008 governments the world over have tried to fight the biggest banking collapse since the great depression with modest success. Eight years on and you would be loath to say that the world has turned a corner, ushering in a return of unrestrained economic growth.